- Home

- William Ritter

The Unready Queen Page 9

The Unready Queen Read online

Page 9

“Whoa,” said Cole.

“And here I thought Warner’s uncle was just a superstitious old man,” Hill mused. “That forest really is trying to kill us.”

Cole glanced back into the woods again. Somewhere in there, a massive monster lurked. He wished that Fable had decided to come with him after all. Sure, she had been able to take on a miniature twig-man with a swat of her paw—but up against a creature five stories tall, it was Fable who would look like a twig.

Tinn made his way alone up Endsborough’s main street. The sun felt warm on his cheeks, and he could smell meat and onions frying in the kitchen of the Lucky Pig. It must be nearly lunchtime already. He wondered if his mother would let him and Cole have a little something from the shop. He waved hello to Old Mrs. Stewart in the rocking chair on her porch. Behind her stood stout barrels of freshly husked hazelnuts, waiting to be carted off to the big city. He smiled at Mr. Washington delivering the mail, then he passed the empty schoolhouse as he cut across the town square to the general store. The bell chimed as he opened the door.

“Tinn?” His mother looked down at him over a counter full of hair treatments and shaving accessories. She was the only person who never hesitated to tell the two of them apart. “What on earth—?”

“Hi, Mom!” said Tinn. “There was a whole thing at the cliff. It’s okay, though. I’m fine. Kull brought me home. Where’s Cole?” Tinn fiddled with a swiveling mirror next to the tins of shaving powder. His face popped into view magnified, his nose several sizes too big.

“Stop touching things. Cole’s back at the house.”

“No, he’s not.”

Annie pursed her lips. Of course he isn’t. “He’s back in trouble, then. Best you’re not in it with him, for once. I’m glad you’re safe and sound. Mr. Zervos is sending me for my lunch break in about twenty minutes. Do you think you can wait out front until then?”

Tinn nodded. He eyed the beef jerky on the counter hopefully.

Annie shook her head. “You have perfectly good food waiting for you at home,” she said.

“What’s this?” Mr. Zervos called behind Annie. He emerged from the ice cellar and closed the door behind him with a click. Mr. Zervos was a friendly man with a big peppery mustache and a bushy beard. According to Mrs. Stewart, who was older than almost anybody in town, Mr. Zervos had once had the sort of figure people called barrel-chested, like the strong men in the fitness magazines he sold at the front of the shop. If that was the case, then the barrel had slipped down into his stomach years ago, and was now supported only by the stalwart efforts of a heroic belt.

“Ah, the boys!” He beamed.

“Just the one this time,” said Annie.

“Tinn,” said Tinn.

“I thought the two of you were a package deal. Ah, well. Come to see your mother work, young man? She’ll be running this shop in no time!”

“You’re very kind, Mr. Zervos. I’m still just happy to have work. Tinn is going to wait out front for me to take my lunch. He won’t be a bother.”

No sooner had she said it than Tinn’s sleeve caught the swiveling mirror and it slapped glass-down against the countertop with a sharp crack.

“Ooch!” Mr. Zervos winced.

“I’m sorry!” Tinn righted the mirror. “It didn’t break. It’s okay!” A small stack of pomade tins toppled over as his elbow swung wide. They rolled onto the floor with a series of bangs. “Shoot! I’m so sorry! I’ll get them!”

Annie caught a teetering jar of lather and righted it. “I told you not to touch anything.”

“I’m so sorry. I’m always screwing stuff up.” He deposited an armful of pomade tins back on the counter. A glimmer caught his eye and he bent down to retrieve a discarded penny, too. “Here,” he added, holding out a coin to Mr. Zervos.

“Ah, ah, ah.” Mr. Zervos shook his head. He was smiling beneath his bushy beard. “None of that. Breaking a mirror is very bad luck, yes. But you did not! So that is lucky! And finding a penny is good luck, too. Double lucky. You keep that. Don’t fret so much about the bad luck that you forget to see the good. Eh?”

Tinn allowed himself a smile, but his ears still felt hot with embarrassment. He tucked the penny into his pocket.

“I’m all done with inventory,” Mr. Zervos said. “Why don’t you go ahead and take your lunch, Annie. Ah—but wait.” He plucked two strips of jerky from the jar on the counter and slipped them to Tinn with a wink. “One for that brother of yours. Stay good for your mom, now.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Oh,” said Annie. “That’s terribly nice of you, sir. Are you sure? I can stay.”

“I have managed on my own before, believe it or not. This town has seen more buildings explode in the past month than it’s seen rushes on flour or baked beans. I’ll be fine for an hour.”

“Thank you very much.”

Annie slipped off her apron and hung it neatly on a hook by the door to the back room. She and Tinn stepped out into the sunlight together.

“Sounds like work’s going well,” said Tinn. He munched on a strip of jerky and avoided making eye contact.

“Yes, other than your fidgeting fingers, I’ve had no problems so far,” said Annie. She rapped a knuckle on the siding as she passed. “Knock on wood. What about you? How was the overnight? Did you get scared?”

“Naw. It was fine,” said Tinn. “I’m learning a lot, and I’m starting to understand the changes a little more. We did songs this time, too. Well, Kull called them songs. There are lots of noises involved. I practiced my howl.”

“We’re howling now?” Annie said. “Okay. You didn’t have to hang off the side of a cliff for howls. If I had known you wanted to howl, we could be howling at home.”

“Mom.” Tinn rolled his eyes.

“We can howl right now, if you like.”

“Stop, Mom. It’s special howls. Never mind.”

“I’m only teasing. I’m glad you had a nice time. I’ll have to thank Mr. Kull for bringing you all the way back. Now if only I knew where your brother ran off to—”

Shouts rang out behind them. Mrs. Stewart stood up from her rocking chair to see what was the matter. A pair of stable hands nearby dropped the bags of feed they were carrying and jogged up to a commotion stirring in the town square.

“What in heaven’s name is going on?” Annie held Tinn’s hand tightly as they both turned toward the hubbub. “Is that . . . is that Cole?”

Three haggard figures staggered to a stop in the center of town. Cole and Mr. Hill carefully eased Oliver Warner—now as white as a sheet—down onto a bench. Hill didn’t look much better. He collapsed at the foot of the bench, running his hands through his dusty hair. Amos Washington from the post office ran to summon Dr. Fisher and Old Jim.

Annie and Tinn pushed through the gawkers. “Cole! Are you all right? What happened? Where have you been?”

“I’m fine, Mom,” Cole said through his mother’s sleeve as she pulled him into a hug. “I wasn’t even there.”

“Tell us what happened, Hill!” a voice from the crowd barked. The square grew silent as all ears leaned in to listen.

Jacob Hill lifted his face from his hands. He considered for a moment before speaking. “The thing was six stories tall,” he said at last. “A giant, ladies and gentlemen! It was on us in an instant. Smashed the drill site to pieces. The rest of the crew took off running, but I went back for Mr. Warner. I owed him that much.”

A murmur rippled through the crowd.

“What was it?” called Helen Grouse, from the back of the group.

“It was an unnatural thing, my friends.” Hill took a deep breath. “There and not there, all at once! It made my eyes ache just to look at it, but it was solid enough. I can still hear the sound of the metal twisting under its grip, bending like it was taffy. It was a brute to put Goliath to shame, a veritable mount

ain of muscles and rage, an unbelievable sight to behold.”

“There’s no such thing as giants,” somebody yelled. “He’s lying!”

“It’s all t-t-true,” spluttered Oliver Warner, propping himself unsteadily on an elbow. “It was a giant. A real giant. I saw it with my own eyes. Hill saved me. He pulled the planks off of me and dragged me out of there. Oh, Lord. Uncle Jim was right. It’s all true. It’s all true. It’s all—” The exertion of speaking washed over him and Warner collapsed onto the bench. Around him, the crowd was filled with gasps as neighbors exchanged furtive looks.

Dr. Fisher arrived and made her way to the front of the crowd. The onlookers mumbled and whispered, and Oliver Warner moaned unintelligibly as the doctor examined him. She snipped the man’s trousers up past the knee and gently shifted his leg. Mr. Warner groaned, his head rolling against the bench.

“It’s definitely broken,” Fisher announced. “I can give him something for the pain, but we’ll want to get him cleaned up and into a proper bed before I set the bone.”

A canvas litter was procured, and Mr. Warner was already being carried away when Evie and Old Jim came hurrying down the road.

“Dad?” Evie called. “Dad!”

Mr. Warner put out a hand limply to pat his daughter on the shoulder as she ran up to the cot. “I’ll be okay, sweetie. Stay with . . . Uncle . . .” His voice petered out and the doctor pressed Evie out of the way.

Tinn stepped out from behind his mother and Cole and edged closer to Mr. Hill. “Was it really a giant?” he asked. “Are you sure?”

Hill shook his head. “Sure? Kid, this morning I was sure fairy tales were a bunch of cockamamie nonsense and that the worst thing in that forest was wolves. I’m not sure of anything anymore. I know what I saw, though.”

Old Jim pursed his lips and nodded. “Was only a matter of time,” he grunted. “Been warnin’ folk about the Wild Wood fer years. There’s evil in that forest.”

“It’s not evil,” Tinn began, but a voice from the crowd cut him off.

“My cousin saw the witch once,” yelled Albert Townshend, “out by the mines. He said he locked eyes on her for just a second, and the very next day he broke his leg.”

“Our back acre’s been cursed for years,” called someone else from the back of the group. “My old man can never get anything but weeds to grow that close to the forest.”

“I’ve still got a scar on my knee from a tussle with a hobgoblin that got into our attic years ago!”

“I told you to leave it alone, Stuart. They’re not a bother unless they’re provoked.”

The crowd began to bubble various accounts of unnatural occurrences and brushes with beasts.

Hill was agog. “And this is just . . . just common knowledge? How do you all live like this?” he asked. “With evil forces lurking behind every log and leaf?”

“The forest folk are not evil!” Tinn said more loudly.

Old Jim raised an eyebrow. Cole stepped to Tinn’s side.

“There are lots of dangerous things in there,” said Evie timidly from beside her great uncle. “But maybe evil isn’t the right word for—”

“No. Evil is right,” growled Mr. Fenerty, a crotchety old man who ran the stationery shop. “Witches and ogres and . . . goblins.” He let his eyes flick from one Burton boy to the other. “Creatures like that don’t have an ounce of good in them.”

There were murmurs of agreement from the crowd.

The air in the crowded town center felt suddenly thin. Tinn flinched as a hand gripped his shoulder, but when he looked up it was only his mother. “Ignore them,” she whispered, but Tinn’s pulse was pounding in his ears.

“You don’t know,” he blurted. “None of you knows! All you know are stories. Stories get things wrong.”

“Stories didn’t break my nephew’s leg.” Old Jim’s voice was cold.

“Tinn’s right, Jim,” said Annie. “We don’t know what really happened up there.”

“I know what I saw,” Hill grumbled.

“Mm.” Old Jim scowled. “Show ’em.”

“What?” said Hill.

“Show ’em what happened to yer rig. They don’t wanna listen to my stories. So let ’em see for themselves.”

Hill looked less than eager at the prospect of returning to the scene, but with an audience awaiting his response, he nodded resolutely. “Yes. Yes, of course. I’ll take you. You, and anyone else brave enough to witness the wreckage with their own eyes.”

The crowd erupted into a susurrus as curious townsfolk stepped up to join the expedition. Annie knelt down in front of the boys.

“The forest isn’t evil,” mumbled Tinn. “I’m not evil.”

“Of course you’re not, sweetie.” Annie kissed his forehead. “You know better than to take those knuckleheads seriously. Old Jim thinks electricity is evil.”

Tinn nodded glumly.

“The rest of the town seems to be taking him pretty seriously,” said Cole.

“Yes. I think it might be best if I go up there with them,” Annie whispered. “I don’t love the idea of giants in Endsborough, but I don’t love the thought of a bunch of frightened townspeople egging each other on to go hunting monsters, either. Somebody needs to keep a level head.”

“Let’s go,” said Cole. “We should tell Fable and her mom what we find. They keep tabs on everything that happens in their woods—they’re not gonna like this.”

“I will tell them what I find,” Annie corrected. “I don’t want you two anywhere near that place.”

“What?” said both boys at once.

“But, Mom—” Cole began.

“No buts. I want you to stick together, go straight back home, and wait for me there. Understood?”

“No way. If anybody knows what to look for out there, it’s us,” argued Tinn. “We know more about things in those woods than anyone else in town.”

“Yes. And they’ve almost been the death of you more times than I care to count. I mean it.” Annie stood up. Twenty or so villagers were already beginning to make their way up the road behind her. “Go home. Stay put.”

“Yes, ma’am,” they said in miserable unison.

Annie took a deep breath and hurried after the crowd.

Tinn and Cole watched their mother join the procession. They kept watching until the group had made its way out of sight beyond the first bend.

Tinn looked at Cole. Cole looked at Tinn.

They did not go home, and they did not stay put.

Fourteen

Tinn and Cole did not immediately follow the adults up the dusty street to the Roberson Hills. The forest and the town nestled into each other like puzzle pieces along that road, the route weaving in and out, following a path older than Endsborough itself. It was an old loggers’ road that dated back to the days when the town had been little more than an outpost and the mill had still been under construction.

“I have an idea,” said Tinn. “But I’m pretty sure it’s a bad one.”

“Sounds about right,” said Cole. “Bad ideas are kind of what we do. Usually my bad ideas, though, so I guess it’s your turn. What are you thinking?”

“I think we’ll get there faster if we cut through the forest,” said Tinn. “The Roberson Hills are pretty much straight north. The road goes way over to the west and then circles back, so if we cut straight up while they follow the road, then we can get there before everybody else.”

“I’m in,” said Cole. He took a deep breath. “Let’s go into the Wild Wood. Eyes out for giants. And no getting captured by shadows or anything this time. Ready?”

“Ready.”

“Ready,” said a third voice, slightly breathlessly, from behind them.

Cole and Tinn turned.

Evie was wearing a sturdy plaid dress, a pair of oversized work boots, and an e

ager expression. A set of plain brown journals bounced at her hip on a book strap.

“Oh. I don’t know if—” Tinn began.

“I’m coming with you,” said Evie. “Something out there attacked my dad, and I’m going to see what it was for myself. I’ve been training for this forever.”

“You’ve been training for . . . giants?” said Cole.

“I’ve got a whole section on giants.” Evie patted her journals.

Cole and Tinn exchanged glances.

“Don’t leave me out. My dad told me to stay with Uncle Jim, and then Uncle Jim told me to go stay with my dad, and so for the first time ever, nobody is here to tell me I can’t. I might not get another chance like this one. Please.”

“We’re kinda in a hurry,” said Cole.

“Great, then we’d better get going.” Evie held tight to her book strap with both hands and marched between them into the forest.

The thing about roads—even winding ones—is that they are designed for traveling. The thing about forests is that they are not. Twenty minutes later, the children were still making their way through the merciless Wild Wood. Twice they reached an impasse and had to double back to find another way around.

“Exploring the unexplored forest,” Cole grunted, “was a lot easier when we had a map and there was a trail.”

“Are you doing okay?” Tinn asked, helping pull Evie over a rock nearly as tall as she was. “We can stop for a rest if you need.”

“I’m fine,” Evie said, but Tinn could see her wince as her feet landed on the forest floor.

“I’m pretty sure we should have gotten there by now,” said Cole. He peered into the forest ahead. It showed no signs of thinning. “This bad idea of yours might have actually been a bad idea.”

“Are we lost?” said Evie.

“No,” said Tinn. “We’re not lost.”

“We might be a little bit lost,” admitted Cole.

“Well, of course we’re a little bit lost,” said Tinn. “We’re on an adventure.”

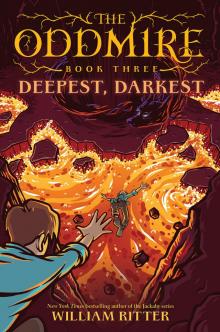

Deepest, Darkest

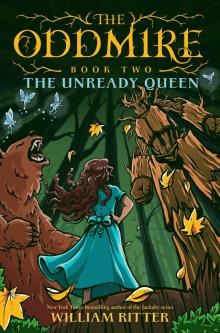

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

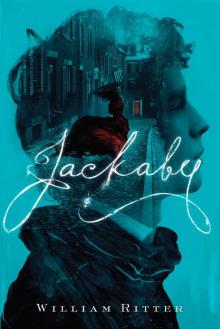

The Unready Queen Jackaby

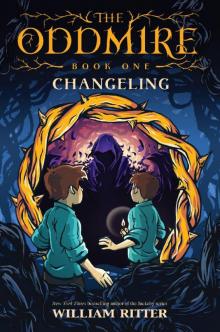

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones