- Home

- William Ritter

Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Read online

The Jackaby Series by William Ritter

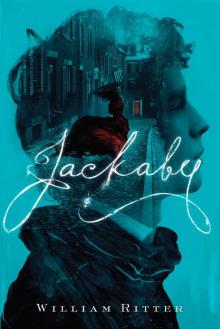

Jackaby

Beastly Bones

Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly

Echoes

A Jackaby Novel

William Ritter

ALGONQUIN 2016

For Justin,

whose past was sometimes dark,

but who makes his future bright.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About Algonquin

Chapter One

Mr. Jackaby’s cluttered office spun around me. Leaning heavily on the desk, I caught my breath in shuddering gulps. My head was throbbing, as though a shard of ice had pierced through one temple and out the other, but the sensation was gradually subsiding. I opened my eyes. The stack of case files I had spent all morning sorting lay strewn across the carpet, and the house’s resident duck was cowering behind the legs of my employer’s dusty chalkboard, shuffling anxiously from one webbed foot to the other.

One lonely file remained on the desk at my fingertips—a mess of fading newsprint and gritty photographs. My pulse hammered against the inside of my skull, and I concentrated, trying to slow my heartbeat as I propped myself up on the desk. Before me lay the police report, which described the grisly murder of an innocent woman and the mysterious disappearance of her fiancé. Beneath it was tucked the lithograph of a house, a three-story building in a quiet New England port town—the same house in which I now stood, only ten years younger—it looked simpler and sadder back in 1882. Then there were my employer’s collected notes, and beside them the photograph of a pale man, his lips curled in a wicked smirk. Strange men stood behind him wearing long leather aprons and dark goggles. My eyes halted, as they always did, on one final photograph. A woman.

I felt sick. My vision blurred again for a moment and I forced myself to focus. Deep breath. The woman in the picture wore an elegant, sleeveless dress as she lay on a bare floor, one arm outstretched and the other resting at the torn collar of her gown. A necklace with a little pewter pendant hung around her neck, and a dark stain shaded her chest and collected around her body in an ink-black pool. Jenny Cavanaugh. My friend. Dead ten years, and a ghost the whole time I had known her.

The air in the room shimmered like a mirage, and I pulled my gaze away from the macabre picture. Keeping one hand on the desk to steady myself, I raised my chin and straightened my blouse as a spectral figure coalesced before me. My pulse was still pounding in my ears. I wondered if Jenny could hear it, too.

“It’s fine. I’m fine,” I lied. I am not fine, every fiber within me shouted. “I’m ready this time.” I am anything but ready. I took a deep breath. The phantom did not look convinced. “Please,” I said. “Try it again.” This is a bad idea. This is a terrible idea. This is—

And then the office vanished in a blinding haze of mist and ice and pain.

Jenny Cavanaugh was dead, and she wasn’t happy about it. Another week would mark the passing of ten years since death had come prowling into her home. It would mark ten years since it had dropped her on her back in the middle of her bedroom, her blood spilling across the polished floor. Her fiancé, Howard Carson, had vanished the same night, and with him any clues as to the purpose or perpetrator of the gruesome crime.

Perhaps it was due to the approach of such a morbid anniversary, but in all the months I had known her, Jenny had never been so consumed by her memories as she had become in the past week. Her carefree attitude and easy laugh had given way to tense silence. She made an effort to maintain her usual mask of confidence, smiling and assuring me that all was well. Her eyes betrayed the turmoil inside her, though—and there were times when the mask fell away completely. What lay beneath was not a pleasant sight.

R. F. Jackaby, my employer and a specialist in all things strange and supernatural, called those moments echoes. I cannot begin to fathom the depths of Jenny’s trauma, but I glimpsed into that icy darkness every time I witnessed an echo. Everything Jenny was fell away in an instant—the woman she had once been and the spirit she had become—until all that was left was a broken reflection of her last living seconds. Fury and fear overwhelmed her as she relived the scene, and all around her spun a storm of ice and wind. The unfathomable forces that held a soul intact had come untethered in Jenny, and what remained was something less than living and something more than human. The first time I watched her fall into that cold place had been bad enough, but it was far from the last. The further we pursued her case, the more frequently and violently the echoes overcame her.

Jenny regarded these moments with frustrated embarrassment after she regained her composure, as might a sleepwalker upon waking to find herself on the roof. She became increasingly determined to hone her spiritual control so that she might find answers to the questions that had haunted her since her death, and I became increasingly determined to help.

“Tread lightly, Miss Rook,” warned Mr. Jackaby one evening, although he was usually the last person to exercise caution. “It would not do to push Miss Cavanaugh too far or too fast.”

“I’m sure she’s capable of much more than we know, sir,” I told him. “If I may . . .”

“You may not, Miss Rook,” he said. “I’ve done my research: Mendel’s treatise on the demi-deceased; Haversham’s Gaelic Ghasts. Lord Alexander Reisfar wrote volumes on the frailty of the undead psyche, and his findings are not for the faint of heart. We are churning up water we ought not stir too roughly, Miss Rook. For her sake and for ours.”

“With all due respect, sir, Jenny isn’t one of stuffy Lord Reisfar’s findings. She’s your friend.”

“You’re right. She isn’t one of Lord Reisfar’s findings, because Lord Reisfar’s findings involved pushing spectral subjects to their limits just to see what would happen to them—and that is not something I intend to do.”

I hesitated. “What would happen to his subjects?”

“What would happen,” answered Jackaby, “is the reason Lord Reisfar is not around to tell you in person.”

“They killed him?”

“A bit. Not exactly. It’s complicated. His nerves gave out, so he abandoned necropsychology in favor of a less enervating discipline, and was shortly thereafter eaten by a colleague’s manticore. He might or might not still haunt a small rhubarb patch in Brussels. Cryptozoology is an unpredictable discipline. But my point stands!”

“Sir—”

“The matter is settled. Jenny Cavanaugh is in an unstable condition at the best of times, and finding painful answers before she is ready might send her over an internal threshold from

which there can be no return.”

I don’t think my employer realized that Jenny had crossed an internal threshold already. Until recently, she had always been reticent about investigating her own death, shying away from solid answers as one who has been burned shies away from the flame. When Jackaby had first moved his practice into her former property, into the home in which she had lived and died, Jenny had not been ready. The truth had been too much for her soul to seek. She had made a decision, however, when she finally enlisted our services to solve her case—and, once made, that decision had become her driving force. She had waited long enough.

Now it was Jackaby who seemed to be dragging his heels to help, but his unavailing attitude only made Jenny more determined to help herself. To her dismay, determination alone could not give her a body, and without one she could do frustratingly little to expedite the case. Which was why she had come to me.

Our first spiritual exercises had been fairly benign, but Jenny still felt more comfortable practicing when Mr. Jackaby was away. We had known each other only six short months, but she had quickly become like a sister to me. She was self-conscious about losing control, and Jackaby only made matters worse by growing increasingly overprotective. We began by attempting to move simple objects one afternoon while he was out.

Jenny remained unable to make physical contact with anything that had not belonged to her in life, but on rare occasions she had managed to break that rule. The key, we found, was not concentration or sheer force of will, but rather perspective.

“I can’t,” she said after we had been at it for an hour. “I can’t move it.”

“Can’t move what?” I asked.

“Your handkerchief.” She waved her hand through the flimsy, crumpled thing on the table. It did not so much as ripple in the breeze.

“No,” I answered. “Not my anything. You can’t move your handkerchief. I gave it to you.”

“My handkerchief, then,” she said. “A lot of good my handkerchief is going to do me when I can’t even stuff it in a pocket!” She gave it a frustrated swat with the back of her hand, and it flopped open on the table.

We both stared at the cloth. Slowly her eyes rose to meet mine, and we were both grinning. It had been the flimsiest of motions, but it was the spark that lit the fire. We scarcely missed a chance to practice after that.

Not every session was as productive as the first, but we made progress over time. Several fragile dishes met their demise in the following weeks, and the frustration of her failures pushed her into spiritual echoes more than once. With each small setback, however, came greater success.

We expanded our tests to leaving the premises, which Jenny had not done since the day she died. This proved an even more daunting task. On our best round, she managed to plant but a single foot on the sidewalk—and it took her most of the afternoon to rematerialize afterward.

When moving outward failed to yield the results we had hoped for, I began to explore moving inward. I knew that this could be even more dangerous territory to tread, but the following day I asked Jenny to think back and tell me what she remembered about that night.

“Oh, Abigail, I’d really rather not . . .” she began.

“Only as much as you feel comfortable,” I said. “The smallest, most inconsequential details. Don’t even think about the big stuff.”

Jenny breathed deeply. Well, she never really breathed; it was more a gesture of comfort, I think. “I was getting dressed,” she said. “Howard was going to take me to the theater.”

“That sounds nice,” I said.

“There was a sound downstairs. The door.”

“Yes?”

“You shouldn’t be here,” said Jenny.

The shiver rippled up my spine even before I felt the temperature drop. I had come to recognize those words. They came from that dark place inside Jenny.

“I know who you are.” Her gown was elegant and pristine, but at the same time it was suddenly torn at the neck and growing darker. She was already fracturing. Jenny’s echoes were like a horrid version of the party favors my mother used to buy—little cards with a bird on one side and an empty cage on the other with a stick running down the middle. When you twirled the stick, the bird was caught. A trick of the eye. As Jenny fluttered in front of me, graceful and grotesque, the two versions of her became one, but some part of my brain knew they did not belong together. Her brow strained and her eyes grew wild with anger and confusion.

“Jenny,” I said, “it’s me. It’s Abigail. You’re safe. There’s no one—”

“You work with my fiancé.”

“Jenny, come back to me. It’s all right now. You’re safe.”

“No!”

“You’re safe.”

“NO!”

By the time she reappeared, I had tidied up all the broken glass and righted all the furniture. She always returned, but it took Jenny time to recover from an echo. I kept myself from fretting by keeping busy with my chores. I sorted through old receipts and dusty case files compiled by my predecessor, Douglas. Douglas was an odd duck. He had had excellent handwriting when he had been Jackaby’s assistant. Of course, that was when he had still had hands—not that he seemed to miss them now that they were wings.

When I say Douglas was an odd duck, I mean it quite literally. His transformation into water fowl had taken place during his last official case. Working for R. F. Jackaby came with unique occupational hazards.

Douglas perched on the bookshelf now to watch me while I worked, issuing an occasional disapproving quack or ruffling his feathers when I filed something incorrectly. He seemed to enjoy life as a bird, but it made him no less insufferably fastidious than he had been as a human. Jenny materialized slowly; she was just a hint of shimmering light in the corner when I first realized she was there. I gave her time.

“Abigail,” she said at last. She was still translucent, only just visible in the soft light. “Are you all right?”

“Of course I am.” I set down the stack of case files on the corner of the desk. Jenny’s own file lay open beside them. “Are you?”

She nodded faintly, but heavy thoughts hung over her brow like rain clouds.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I shouldn’t have . . . I’ll stop pushing you.”

“No.” She solidified a little. “No, I want to keep practicing.” She bit her lip. “I’ve been thinking.”

“Yes?”

“I’m not as strong as you are, Abigail.”

“Oh, nonsense—”

“It’s true. You’re strong, and I’m grateful for your strength. You’ve already given me more of it than I have any right to ask, only . . .”

“Only what?”

“Only, I wonder if I could ask for a little more.”

Possession. She wanted to attempt possession, and in my foolish eagerness I agreed. I managed to convince myself that I was braced to handle Jenny Cavanaugh’s spirit entering my mind and sharing my body—but nothing could have been further from the truth; there could be no bracing against the sensations to come. She was tentative and gentle, but the experience proved to be like inviting a swirling maelstrom of pain and cold directly into my skull. My vision went white and I felt as though my eyes had been replaced with lumps of ice. If I cried out, I could not hear my own voice. I could not hear anything at all. There was only pain.

Our first attempt was over as soon as it had begun. I was reeling, my head throbbing and my vision blurry. The files I had sorted were strewn across the floor—all of them but Jenny’s. Her photograph, the photograph from her police record, lay atop the pile on Jackaby’s desk. Jenny was in front of me before I could gather my wits about me. She looked mortified and concerned.

“It’s fine. I’m fine,” I lied, doing my best to make it true as I leaned on the desk and tried not to pitch forward and retch on the carpet. “I’m ready this time. Please. Try it again.”

I was not ready. Neither was she.

Jenny hesitated for a moment a

nd then drifted closer, smooth and graceful as always. Her hair trailed behind her like smoke in the wind. She reached a delicate hand toward my face, and—if only for an instant—I could have sworn I felt her fingers brush my cheek. It was a sweet caress, like my mother’s when she used to tuck me into bed at night. And then the biting cold returned. My nerves screamed. This is a bad idea. This is a terrible idea. This is—

The office faded into a blinding haze of whiteness, and together we tumbled into a world of mist and ice and pain . . .

. . . and out the other side.

Chapter Two

It seemed like only yesterday I had been back home in England, packing for my first term at university. Had someone told me then that I would throw it all away and run off to America to commune with ghosts and answer to ducks and help mad detectives solve impossible murders, I would have said they were either lying or insane. I would have sorted them on the same shelf in my mental library as those who believe in Ouija boards or sea serpents or honest politicians. That sort of foolishness was not for me. I adhered to facts and science; the impossible was for other people.

A lot can change in a few short months.

The pain had ebbed to numbness and the blinding light had faded away. I did not remember moving into the foyer, but it was suddenly all around me. I blinked. How long had I been out? I stood in the front room of Jackaby’s offices at 926 Augur Lane—of that there was no doubt—but the room was barely recognizable. In place of the battered wooden bench sat a soft divan. The paintings of mythical figures had been replaced by tasteful landscapes, and the cluttered shelves full of bizarre masks and occult artifacts stood completely barren—even Ogden’s terrarium was missing. When I had been gassed out of the house by the flatulent little frog on my first day, I would not have expected to be so bothered by his absence, but now I found it most disquieting. The desk stood in its usual place, but it was uncharacteristically clean and empty. Behind it stood a pile of boxes and paper bundles bound in twine. Had Jackaby packed? Were we moving?

The front door swung suddenly open and there stood R. F. Jackaby in his typical motley attire. His coat bulged from its myriad pockets, and his ludicrously long scarf dragged across the threshold as he stepped inside. Atop his head sat his favorite knit mess, a floppy hat of conflicting colors and uneven stitches. I had been secretly pleased to see that particular piece of his wardrobe completely incinerated by an ungodly blaze during our previous caper. I shook my head. It had been destroyed, hadn’t it?

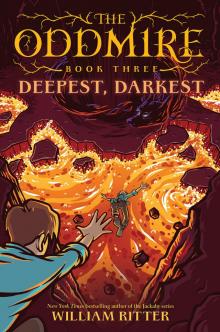

Deepest, Darkest

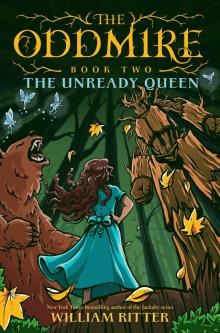

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

The Unready Queen Jackaby

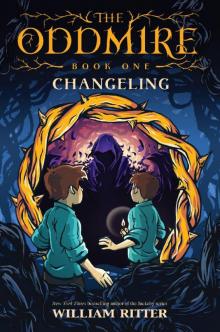

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones