- Home

- William Ritter

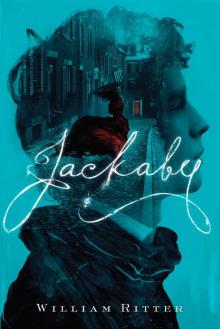

Jackaby

Jackaby Read online

Jackaby

William Ritter

ALGONQUIN 2014

For Jack, who makes me want to create impossible things,

and for Kat, who convinces me I can and insists that I do.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Supplemental Material

Reader’s Guide

About the Author

About Algonquin

Chapter One

It was late January, and New England wore a fresh coat of snow as I stepped along the gangplank to the shore. The city of New Fiddleham glistened in the fading dusk, lamplight playing across the icy buildings that lined the waterfront, turning their brickwork to twinkling diamonds in the dark. In the inky black of the Atlantic, the reflected glow of the gaslights danced and bobbed. I made my way forward, carrying everything that traveled with me in a single suitcase. The solid ground beneath my feet felt odd after so many weeks at sea, and looming buildings rose up around me on all sides. I would come to know this city well, but in that cold winter of 1892, every glowing window and dark alley was strange, full of untold dangers and enticing mysteries.

It was not an old city—not by the standards of those I had seen along my travels—but it bore itself with all the robust pomp and granite certainty of any European harbor town. I had been to mountain villages in the Ukraine, burgs in Poland and Germany, and estates in my native England, but still I found it hard not to be intimidated by the thrum and pulse of the busy American port. Even as the last of the evening light faded from the sky, the dock was still alive with shadowy figures, hurrying about their business.

A storekeeper was latching the shutters as he closed up shop for the night. Sailors on leave sauntered down the harbor, looking for wild diversions on which to spend their hard-earned money—and women with low necklines looked eager to help them spend it faster. In one man I saw my father, confident and successful, probably strolling home late, once again, having devoted the evening to important work rather than his waiting family.

A young woman across the dock pulled her winter coat tightly around herself and ducked her chin down as the crowd of sailors passed. Her shoulders might have shaken, just a little, but she kept to her path without letting the men’s boisterous laughter keep her from her course. In her I saw myself, a fellow lost girl, headstrong and headed anywhere but home.

A chilly breeze swept over the pier, and crept under the worn hem of my dress and through the seams of my thick coat. I had to throw up a hand to hold the old tweed cap on my head before it blew away. It was a boy’s fashion—my father called it a newsboy—but I had grown comfortable in it in the past months. For once I found myself wishing I had opted for the redundant underskirts my mother always insisted were so important to a lady’s proper dress. The cut of my simple green walking gown was excellent for movement, but the fabric did nothing to hold back the icy chill.

I turned my wooly collar up against the snow and pressed forward. In my pockets jingled a handful of coins left over from my work abroad. They would buy me nothing but sympathy, I knew, and only if I bargained very well. Their foreign faces told a story, though, and I was happy for their tinkling company as I trudged through the crunching powder toward an inn.

A gentleman in a long brown coat with a scarf wound up nearly to his eyebrows held the door for me as I stepped inside. I dusted the fresh flakes from my hair as I hung my hat and coat beside the door, tucking my suitcase beneath them. The place smelled of oak and firewood and beer, and the heat of a healthy fire brought a stinging life to my cheeks. A half-dozen patrons sat scattered about three or four round, plain, wooden tables.

In the far corner stood a box piano, its bench unoccupied. I knew a few melodies by heart, having taken lessons all through grammar school—Mother had insisted that a lady should play an instrument. She would have fainted at the notion that I might someday put her fine culture and training to such vulgar use, especially unescorted in this strange, American tavern. I quickly turned my thoughts away from my mother’s overbearing prudence before I might accidentally see reason in it. I put on my most charming smile, instead, and approached the barman. He raised a bushy eyebrow as I neared, which sent a ripple of wrinkles to the dome of his bald head.

“Good afternoon, sir,” I said, drawing up to the bar. “My name is Abigail Rook. I’m just off a boat, and I find myself a bit short on cash, at present. I wonder if I could just set up a hat on your piano and play a few—”

The bartender interrupted. “It’s out of service. Has been for weeks.”

I must have shown my dismay, because he looked sympathetic as I turned to go. “Hold on, then.” He poured a frothy pint and slid it across the bar to me with a nod and a kindly wink. “Have a seat for a while, miss, and wait out the snow.”

I hid my surprise behind a grateful smile, and took a stool at the bar beside the broken piano. I glanced around at the other patrons, hearing my mother’s voice in my head again, warning me that I must look like “that sort of girl,” and worse, that the drunken degenerates who frequented these places would fix their eyes on me like wolves on a lost sheep. The drunken degenerates did not seem to notice me in the least, actually. Most of them looked quite pleasant, if a bit tired after a long day, and two of them were playing a polite game of chess toward the back of the room. Holding the pint of ale still felt strange, as though I ought to be looking nervously over my shoulder for the headmaster to appear. It was not my first drink, but I was unaccustomed to being treated as an adult.

I peered at my own reflection in a frosty window. It had been scarcely a year since I had put the shores of England behind me, but the rugged young woman looking back from the glass was barely recognizable. The salty sea air had stolen some of the softness from my cheeks, and my complexion was tan—at least tan by English standards. My hair was not braided neatly and tied with ribbons, as my mother had always preferred it, but pinned up in a quick, simple bun that might have been a little too matronly if the wind had not shaken loose a few curving wisps to hang free about my collar. The girl who had fled the dormitories was gone, replaced by this unfamiliar woman.

I forced my attention past the reflection to the flurries of white flakes somersaulting in the lamplight beyond. As I nursed the bitter drink, I became gradually aware of a body standing behind me. I turned slowly and nearly spilled the pint.

It was the eyes, I think, that startled me the most, opened wide and staring with intense inquisition. It was the eyes—and the fact that he stood not half a pace from my stool, leaning ever so slightly in, so that our noses nearly bumped as I turned to face him.

His hair was black, or very dark brown, and nearly wild, having only enough civility to point itself in a tousled heap backward, save a few errant strands that danced about his temples. He had hard cheekbones and deep circles under pale, cloud gray eye

s. His eyes looked like they could be a hundred lifetimes old, but he bore an otherwise young countenance and had a fervent energy about him.

I pulled back a bit to take him in. He was thin and angular, and his thick brown coat must have been as heavy as he was. It fell past his knees and sagged with the weight of several visibly overstuffed pockets. His lapel was bordered by a long, wooly scarf, which hung almost as long as the coat, and which I recognized as the one I had passed coming in. He must have doubled back to follow me.

“Hello?” I managed to say, when I had regained balance atop my stool. “Can I help—?”

“You’re recently from the Ukraine.” It was not a question. His voice was calm and even, but something more . . . amused? He continued, his gray eyes dancing as though exploring each thought several seconds before his mouth could voice it. “You’ve traveled by way of Germany, and then a great distance in a sizable ship . . . made largely of iron, I’d wager.”

He cocked his head to one side as he looked at me, only never quite square in the eyes, always just off, as though fascinated by my hairline or shoulders. I had learned how to navigate unwanted attention from boys in school, but this was something else entirely. He managed to seem both engrossed and entirely uninterested in me all at once. It was more than somewhat unsettling, but I found myself as intrigued as I was flustered.

With delayed but dawning comprehension, I gave him a smile and said, “Ah, you’re off the Lady Charlotte as well, are you? Sorry, did we meet on deck?”

The man looked briefly, genuinely baffled, and found my eyes at last. “Lady who? What are you talking about?”

“The Lady Charlotte,” I repeated. “The merchant carrier from Bremerhaven. You weren’t a passenger?”

“I’ve never met the lady. She sounds dreadful.”

The odd, thin man resumed examining my person, apparently far more impressed by my hair and the seams of my jacket than by my conversation.

“Well, if we didn’t sail together, how did you ever—ah, you must have snuck a peek at my luggage labels.” I tried to remain casual, but leaned away as the man drew closer still, inspecting me. The oak countertop dug into my back uncomfortably. He smelled faintly of cloves and cinnamon.

“I did nothing of the sort. That would be an impolite invasion of privacy,” the man stated flatly as he picked a bit of lint from my sleeve, tasted it, and tucked it somewhere inside his baggy coat.

“I’ve got it,” I announced. “You’re a detective, aren’t you?” The man’s eyes stopped darting and locked with mine again. I knew I was onto him this time. “Yes, you’re like whatshisname, aren’t you? The one who consults for Scotland Yard in those stories, right? So, what was it? Let me guess, you smelled salt water on my coat, and I’ve got some peculiar shade of clay caked on my dress, or something like that? What was it?”

The man considered for a moment before responding. “Yes,” he said at last. “Something like that.”

He smiled weakly, and then whirled on his heels and away, tossing his scarf around and around his head as he made for the exit. He crammed a knit hat over his ears and flung the door open, steeling himself against the whirling frost that rushed in around him. As the door slowly closed, I caught one last glimpse of cloudy gray eyes just between the wooly edges of his scarf and hat.

And then the man was gone.

Following the curious encounter, I asked the barman if he knew anything about the stranger. The man chuckled and rolled his eyes. “I’ve heard lots of things, and one or two of them might even be true. Just about everyone’s got a story about that one. Isn’t that right, boys?” A few of the locals laughed, and began to recall fragments of stories I couldn’t follow.

“Remember that thing with the cat and the turnips?”

“Or the crazy fire at the mayor’s house?”

“My cousin swears by him, but he also swears by sea monsters and mermaids.”

For the two older gentlemen on either side of the chessboard, my query sparked to life an apparently forgotten argument, one that burst quickly into an outright quarrel about superstitions and naivete. Before long, each had attracted supporters from the surrounding tables, some insisting the man was a charlatan, others praising him as a godsend. From the midst of the confusing squabble I was at least able to catch the strange man’s name. He was Mr. R. F. Jackaby.

Chapter Two

By the following morning I had managed to put Mr. Jackaby out of my thoughts. The bed in my little room had been warm and comfortable, and had cost only an hour’s worth of cleaning dishes and sweeping floors—although the innkeeper had made it very clear that this was not to be a lasting arrangement. I threw open the drapes to let the morning light pour in. If I planned to continue my bold adventure without reducing myself to living beneath a bridge and eating from rubbish bins—or worse, writing to my parents for help—I would need a proper job.

I hefted my suitcase to the bed and opened it with a click. The garments within were pressed up to either side, as though embarrassed to be seen with one another. To one end, fine fabrics with delicate, embroidered hems and layers of lace began immediately to expand, stretching in the morning light as the compressed fabric breathed again. Opposite the gentle pastels and impractical frippery sat a few dust-brown denim work trousers and tragically sensible shirts. A handful of undergarments and handkerchiefs meekly navigated the space between, keeping quietly to themselves.

I stared at the luggage and sighed. These were my options. One by one I had worn through everything in between, until I was faced with these choices, which seemed to reflect my lot in life. I could costume myself as a ruddy boy or as a ridiculous cupcake. I plucked a plain camisole and drawers from the center of the suitcase and then pulled the top closed in disgust, stuffing the fancy dresses back down against their muffled protests. The simple green walking dress I had worn for my arrival hung over the bedpost, and I held it up in the sunlight. Its hem was tired, still a bit damp from the previous night’s snow, and growing frayed from use. I pulled it on anyway and wound my way back downstairs. I would look for a job first, and new clothes after.

By the light of day, New Fiddleham felt fresh and full of promise. The air was still crisp as I embarked on my trek into town, but the cold was a little less invasive than it had been during the night. I felt the tingle of excitement and hope tickle along my spine as I hefted my suitcase up the cobbled streets. This time, I resolved, I would find conventional employment. My previous and only real prior job experience had come from foolishly following an advertisement with bold, capitalized words like EXCITING OPPORTUNITY, and CHANCE OF A LIFETIME, and, probably most effective in capturing my naive attention, DINOSAURS.

Yes, dinosaurs. My father’s work in anthropology and paleontology had instilled in me a thirst for discovery—a thirst he seemed determined I should never quench. Throughout my childhood, the closest I had come to seeing my father’s work had been during our trips to the museum. I had been eager to study, excelled in school, and had anticipated higher education with excitement—until I found out that the very same week my classes were to begin, my father would be leaving to head the most important dig of his career. I had begged him to let me go to university, and been giddy when he finally convinced my mother—but now the thought of suffering through dusty textbooks while he was uncovering real history made me restless. I wanted to be in the thick of it, like my father. I pleaded with him to let me come along, but he refused. He told me that the field was no place for a young lady to run around. What I ought to do, he insisted, was finish my schooling and find a good husband with a reliable job.

So, that was that. The week before my semester was to begin, I plucked the EXCITING OPPORTUNITY advertisement from a post, absconded with the money my parents had set aside for tuition, and joined an expedition bound for the Carpathian Mountains. I had been afraid that they wouldn’t take a girl. I picked up a few trousers in a secondhand shop—all of them too big for me, but I rolled the cuffs and found a belt. I pr

acticed speaking in a lower voice and stuffed my long, brown hair into my grandfather’s old cap—it was just the sort all the newsboys wore, and I was sure it would complete my disguise. The end result was astounding. I had managed to completely transform myself into . . . a silly, obvious girl wearing boys’ clothing. As it turned out, the leader of the dig was far too occupied with managing the barely funded and poorly orchestrated affair to care if I was even human, let alone female. He was just happy for a pair of hands willing to work for the daily rations.

The following months could be described as an “exciting opportunity” only if one’s definition of excitement included spending months eating the same tasteless meals, sleeping in uncomfortable cots, and shoveling rocky dirt day in and day out on a fruitless search. With no recovered fossils and no more funding, the expedition collapsed, and I was left to find my own way back from the eastern European border.

“Stop your dreaming and settle!” seemed to be the prevailing message of the lesson I’d spent several months and a full term’s tuition to learn. It was on the tails of that abysmal failure that I found myself at a German seaport, looking for passage back to England. My German was terrible—nearly nonexistent. I was halfway through negotiating the price of a bunk on a large merchant carrier called the Lady Charlotte when I finally understood that the captain was not sailing to England at all, but would be briefly making port in France before crossing the wide Atlantic bound for America.

Most jarring of all was my realization that the prospect of sailing across the ocean to the States was much less frightening to me than that of returning home. I don’t know whether I was more afraid of confronting my parents, having stolen away with the tuition money, or of confronting the end of my adventure, which felt as though it had never really even had a middle.

I purchased three items that afternoon: a postcard, a stamp, and a ticket on the Lady Charlotte. My parents most likely received the post about the same time I was watching the shores of Europe drift behind me, and the vast, misty blue ocean expand before me. I was not so naive and hopeful as I had been when my voyage began, but the world was growing larger by the day. The postcard was brief, and read simply:

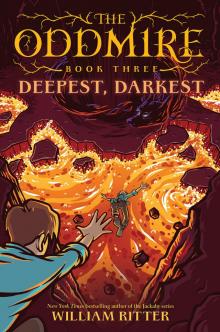

Deepest, Darkest

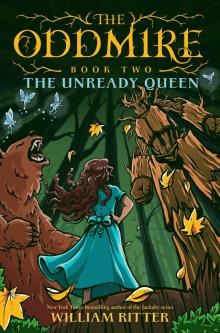

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

The Unready Queen Jackaby

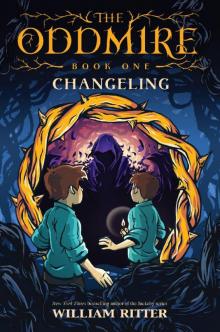

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones