- Home

- William Ritter

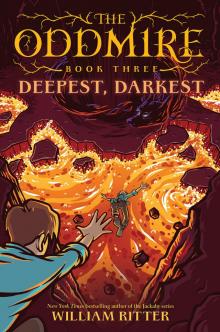

Deepest, Darkest

Deepest, Darkest Read online

The Oddmire

Book Three

Deepest, Darkest

written and illustrated by

William Ritter

Algonquin Young Readers 2021

For my father,

Russ.

Contents

Dedication

Map

Earlier

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Acknowledgments

Also by William Ritter

EARLIER

The forest whipped past the Thing in a blur. It was feeling things it had not felt in a very long time—and some it had never felt at all. The pain, the cold, the fear . . . these were all too familiar. But nestled beside them now was something else, an exquisite ache. The Thing could scarcely breathe.

It had failed. It had tried to consume a changeling boy, and it had failed—and then everything had come crashing down. The boy’s words echoed in its skull. Nobody ever came for you, did they? That isn’t fair. The Thing burrowed its face into the soft earth, but that voice was everywhere. His hand, gentle and warm, had scooped it up, held it close. The boy’s eyes had looked down at it with such pity.

I am sorry that you suffered, the boy had said. You didn’t deserve that. You didn’t deserve to be turned into this.

The Thing dug more deeply now. It roared a furious roar to drown out the words and the feelings, but all that escaped into the cold night was a piteous wail, little more than the squeaking of a mouse. It was all too much.

It clutched at shadows, trying desperately to pull the darkness around itself as it once had, to create for itself an armor of icy midnight. The shadows melted through its fingers like smoke. Something had changed—not in the shadows, but within the Thing itself—and it couldn’t put itself back the way it was.

The Thing did not want to be different. It burrowed deeper.

The Thing could still feel the warmth of the child’s hands, clinging to it like tar. It had felt something else, too, while it was being held. It had felt—not anger . . . not hate . . .

The memory burned like acid in the pit of its stomach. Deeper and deeper it tunneled.

The Thing had felt . . .

. . . love.

But how? How could the boy treat it that way—after everything it had done, had tried to do, had promised to do? The boy had seen the Thing at its worst and he had not given up on it. He had greeted its sharpest barbs with tenderness.

Nobody had ever come for the Thing. The boy was right about that. The boy’s family had come for him, and his friends, and even the forest folk. But nobody had ever come for the Thing. Not ever.

Except for the boy.

The boy had come for the Thing. He had knelt down and reached out for the Thing, held it, given it a chance. If, against every rational instinct, the boy could love a wretched creature such as it . . . then maybe the Thing was capable of being loved after all.

All at once, the ground beneath the Thing’s fingers crumbled away, and it nearly dropped into a gaping underground cavern. The Thing caught itself and breathed in deeply. There were bodies moving below it in the dark; the Thing could sense them. It could also sense hopelessness and despair. The Thing closed its eyes and tasted currents of misery in the clammy air.

Yes. This was familiar. This was a flavor the Thing knew.

It drank deeply.

Around it, the darkness slowly thickened and coalesced once more.

Yes. This was right. Nothing had changed. The Thing could do great, terrible things down here.

One

“I’m going down,” said Cole.

“Watch your step,” Tinn whispered.

The shaft was pitch-black and cold, and even the air felt heavy with the weight of the whole world pressing down on the twins. The yellow halo from the lantern bounced and bobbed as Cole eased himself down the stony slope, its light fading away a hundred feet or so into the fathomless dark. He held out a hand to brush the walls of the tunnel as he pressed forward. His feet shuffled as he slid down the path.

“It levels out again down here,” he called up once he had found his footing. “Ow!”

“What happened? Are you okay?” Tinn skidded down after his brother. The crunch of his shoes and the skittering of loose pebbles resonated like an avalanche as they echoed all around him.

“I’m fine.” Cole rubbed his head. “Watch the ceiling. It’s low in here.”

Tinn found his footing and put a hand on his brother’s shoulder as they inched farther into the gloom. The flickering light danced across the broken handle of a pickax, abandoned against the tunnel wall. “That could have been his,” whispered Cole. “Who knows how long this tunnel has been closed. He might have been the last person in here. We could be walking where he walked.”

Tinn said nothing. He knew who Cole was talking about. It was all Cole wanted to talk about lately. Their father was more of a legend to the boys than a real person.

Joseph Burton had vanished nearly thirteen years earlier, when the twins were only babies. Popular rumor around Endsborough was that the man had run away because he knew one of his boys was a goblin in disguise. Old Jim had let slip that the last time they spoke, all those years ago, Joseph had been looking for a way to get rid of the imposter—to get rid of the changeling. Tinn’s throat tightened. To get rid of him.

Tinn had known the story his whole life, but he had only known he was the changeling for the past year. Knowing the truth cast a long shadow over Tinn’s memories, and it twisted the thought of reuniting with the long-lost Joseph Burton into a complicated ball of feelings in his chest.

“I don’t know if we should keep going,” said Tinn. “They close tunnels like these for a reason.”

“Just a little farther,” said Cole.

“We’ll be in huge trouble if Mom finds out we snuck down here.”

“Who’s gonna tell?” Cole answered. “If there’s anybody working in the mines today, they’re definitely not working in this one.”

“Shh.” Tinn put a finger to his lips. “You hear that?”

They both fell silent.

“Hear what?” whispered Cole.

Tinn closed his eyes, straining his ears for a few more seconds. “Nothing, I guess,” he said at length. “I thought I heard footsteps or something tapping.”

Cole shrugged. “It’s called Echo Point for a reason.”

He started forward again, watching his step and hunching low to avoid stalactites and rocky outcrops. Tinn followed suit.

“What if it’s a knocker?” Tinn whispered. “We should really head back.”

“What’s a knocker?” asked Cole, still pressing forward.

“A Tommyknocker,” said Tinn. “Evie has a whole page about them in her journal of creatures. She says all the miners know about

knockers. They’re spirits or ghosts who dress up like miners and hide in mines to cause trouble. Or sometimes they’re nice, I think.”

“Ow!” Cole lurched to a stop and rubbed his forehead with one hand. “Stupid tunnel.”

“They say if you hear Tommy banging around in the caves ahead, there’s going to be a collapse.”

“That’s just a superstition,” said Cole. “She probably heard it from her uncle Jim.”

“We heard about the Witch of the Wood from Old Jim, too,” Tinn reminded him, “and we all thought she was just a superstition right up until we met her.”

“That’s different,” said Cole.

“It’s creepy down here. Let’s go meet Evie and Fable like we said we were gonna.”

“Just a little farther.”

Tinn rubbed the back of his neck, but he kept up. “Kull told me a goblin legend about a group of explorers who dug too deep into the earth once,” he said. “They got greedy looking for gold and gems and cut right into the heart of some sacred mountain. Instead of finding treasure, they unleashed a monster.”

“You told me that one already,” said Cole.

“No I didn’t. I just learned it last week. You’re thinking about the goblins who accidentally woke up a rock giant.”

“Sorry. I can’t keep it all in my head. You tell me a lot of goblin stuff.”

“Actually, there’s one more goblin thing I’ve been wanting to talk to you about—” Tinn began.

“Listen,” said Cole, cutting him off. “I’m glad you like the stories. They’re fun and all, but they’re just not my thing. They’re yours. I want to focus on finding Dad right now.”

“Oh,” said Tinn. “That’s fine. I just thought you wanted me to tell you stuff I learn in lessons. I think it’s neat that we get to know about this whole other world that we’re a part of.”

“You’re a part of it,” said Cole. “Not me. The goblins have made that very clear. I can’t set foot in the horde without getting a spear pointed at my nose. Watch your step, there’s a dip there.”

“You’re still a part of it. That’s just the old-fashioned goblins, and they’ll come around eventually. Kull and Chief Nudd aren’t like that.”

Cole chuckled. “Kull would probably be just as happy to make a stew out of me if he didn’t know it would make you mad.”

“Kull’s not like that. He looked out for us from the shadows—both of us—for our whole lives.”

“Sure, that’s fair. It’s super creepy, but it’s fair. C’mon. I know Kull cares about you, and he’s basically like your goblin dad. Nobody’s taking that away—but our real dad is still out there.”

“Kull is real,” said Tinn. “He’s more real than a stupid picture on a fireplace.”

Cole glanced back over his shoulder with a scowl. “I don’t get it. We spent all these years wondering what happened to him, and now that we finally might have a chance to find our actual dad, why are you acting all weird?”

“Because he’s not my actual dad!” Tinn hadn’t meant to raise his voice. He hadn’t meant to say it out loud at all, but he had been thinking it for weeks, and now he found it tumbling out of his mouth before he could stop it.

“Oh, shut up.” Cole rolled his eyes and turned to trudge deeper into the tunnel. “Of course he’s your dad. Just because you came from somewhere else—you should know better than anyone that family isn’t just about blood.”

“It’s not about blood. You don’t get it. Maybe he was your dad before he left, and maybe he loved you and cared about you—but the only relationship that man ever had with me was trying to figure out how to get rid of me.”

“That’s not—” Cole began.

“It’s true.” Tinn stopped walking, and after a few paces, Cole turned to look at him. “I’ll always be your brother—and I’m not backing out of finding him. I want to help you see your dad again, I really do. But when we do . . . I just . . . I just don’t know where I’m gonna fit into it.”

“With me. With us. A part of it. Like always. Nothing has to change.”

Tinn sighed. “Right,” he said, unconvincingly.

“Looks like we’ll be heading back after all.” Cole held the lantern up. The tunnel’s ceiling slanted gradually downward for about ten more feet and then ended abruptly when it met a wall of craggy rocks. “Another dead end.”

“Good,” said Tinn. “Let’s go home.”

“Wait. Hold on just a second.” Cole lowered the lantern. He tapped the floor ahead of him with his boot. It clunked.

“Boards?” said Tinn.

Cole looked up, and the lamplight glinted wild in his eyes. “They’re covering a gap in the rocks. I can feel air, too,” he said. “I bet there’s another shaft or a cavern or something right below us.”

Tinn knelt next to him and brushed dust from the ancient wood.

“It’s hard to get a good angle,” said Cole. He clambered out onto the boards, turning the lantern this way and that. He hunkered down on his hands and knees, prying at the beams.

“Be quiet a second,” said Tinn. “There it is again! I think it’s getting louder. You can’t hear that?”

Cole raised his head. “I don’t hear anyth—”

But a noise cut him off. It was a creaking, groaning sound that tapered off into tapping, like the settling of an old house on a cold night. It was impossible to gauge where it came from—the noise echoed through the narrow tunnel, chasing and doubling over itself until it gradually faded away.

Tinn didn’t breathe for several seconds. “Ghost?” he whispered.

“That’s no ghost,” said Cole at last. “That’s just the sound old wood makes when it’s straining.”

Tinn glanced down. “You mean like old wooden planks with a couple of kids climbing all over them?”

Cole hesitated. He shifted his weight. The timbers beneath his knees groaned loudly. He gulped. “Sorta like that.”

And then there was a crack.

“Move!” yelled Tinn. “Get off it!”

The platform splintered.

The board under Cole’s right knee went first, and as he tried to catch himself, the one under his left snapped, too. His legs kicked as they found themselves suddenly hanging over empty air.

Cole dropped the lantern, clutching with both hands for a hold that wouldn’t give way. The light clattered against the crumbling wood and then slid down through a crack into heavy darkness. It fell for a long time before it struck the ground with the distant crunch of breaking glass. The flare of the oil catching fire all at once painted the shaft in golden light, illuminating Cole’s terrified face from below.

“I’m slipping!” Cole gasped.

Tinn planted his feet at the edge of the gap and grabbed Cole’s hand just as the whole platform sagged. Cole clung to his brother with both hands as bits of broken boards clattered against the side of the shaft, tumbling twenty, fifty, a hundred feet down to land with distant bangs against the rocky floor.

Cole’s fingers tightened. “Don’t let go!” he cried.

Tinn could feel himself losing the tug-of-war as, against his desperate efforts to fight it, his brother’s weight tipped him slowly forward.

Tinn’s stomach felt strange. Time slowed. The world seemed clearer somehow, as if light were flooding the darkness of the tunnel around them. And then, just as Tinn felt his weight shift past the final tipping point—moments before he and his brother plummeted down the rocky shaft—a hand grabbed his shirt collar from behind and jerked him back to solid ground.

He felt his brother’s hand ripped away, but the dusty figure caught Cole’s arm as well. With another heave, they were safely free of the pit, panting and rubbing their bruises.

The boys turned their eyes to their rescuer. He wore faded coveralls and a dust-brown coat. On his head was clipped a lantern, which sw

iveled from one boy to the other. They squinted into the bright light.

“Thank you for saving us,” panted Tinn.

“Dang,” the figure grunted. “You look just like him.” His voice was deep and dry.

“Sir?” said Cole.

“Reckless like him, too,” the man said.

“We look like who?” asked Cole.

“Like the last fool I had to pull outta this mine shaft. Yer old man, if I’m not very much mistaken.”

The figure tipped his helmet up so that the light flooded the ceiling instead of their eyes, and at last the boys could see the face of their savior. Peppery stubble swept the man’s chin and hard wrinkles creased his forehead, but his eyes were soft.

“You are Joseph Burton’s boys, I presume?” the man said.

Cole’s breath caught in his throat. “You knew our dad?” he managed.

The man nodded solemnly. “Might be the last person ever saw him alive, sad to say.”

Cole’s mouth opened, but no words came out.

The tunnel was quiet except for the muffled sputtering of the lamp and the faint crackle of flames in the distance. The fires below had begun to consume the fallen boards, and in the faint orange glow, shadows fluttered like phantoms on the ceiling above the hole.

“Could we maybe talk somewhere else?” suggested Tinn. “Somewhere a little less horrifying and life-threatening?”

Two

Fable swung gently back and forth in a hammock of vines. It was a good day. Evie Warner had finally gotten permission to spend an afternoon exploring the Wild Wood, and Fable had been doing her best to show Evie everything before it was time for her to go home. Evie hung on Fable’s every word, writing furiously in her notebook with a fancy new fountain pen her mother had sent her from the city.

Already the two of them had skipped across the salamander flats and rustled brownie thistles, and Fable had told Evie which of the shiny violet berries were tasty snacks and which ones made you barf sparkles. Evie could not have wished for a better guide. Fable had been raised in this forest. Her mother was the infamous Queen of the Deep Dark and resident Witch of the Wild Wood—and the forest had begun to accept Fable as the heir to that magical mantle. Fable could have crossed every hill and valley of the Wild Wood with her eyes closed.

Deepest, Darkest

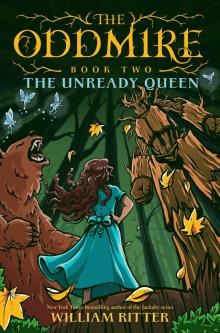

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

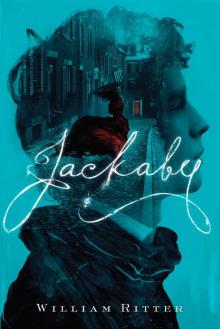

The Unready Queen Jackaby

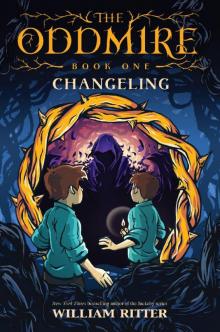

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones