- Home

- William Ritter

The Dire King Page 6

The Dire King Read online

Page 6

“Yes, fine! But she has such prodigious potential!” Jackaby lamented. “Having feelings is one thing—I can grudgingly tolerate feelings—but actually getting married? The next thing you know they’ll be wanting to do something rash, like live together ! Miss Rook, you have started something here that I am loath to see you leave unfinished. You’ve started becoming someone here whom I truly want to meet when she is done. Choosing to leave everything you have here to go be a good man’s wife would be such a wretched waste of that promise.” He faltered, looking to Jenny, and then to the floorboards. “On the other hand, you should never have chosen to work for me in the first place. It remains one of your most ill-conceived and reckless decisions to date—and that is saying something, because you also chose to blow up a dragon once.” He sighed. “Jenny is right. You could make a real life with that young man, and you shouldn’t throw that away just to hang about with a fractious bastard and a belligerent duck.” He sagged until his forehead was resting on his desk.

Hovering behind him, Jenny moved to put a hand gingerly on his shoulder. Her fingers passed right through him, and she bit her lip and withdrew the hand. Jackaby did not appear to have noticed the attempted gesture at all.

“When Charlie proposes,” he said, looking up from the desk listlessly, “just remember that not making a choice is always an option.”

I blinked.

“We’re never not making choices,” said Jenny softly from behind him.

“Charlie,” I managed finally, “is going to propose?”

Jackaby nodded. “Marriage,” he added. “To you. Have you been listening?”

I shook my head. Charlie and I had been on only half a dozen proper dates—and only if you counted situations of mortal peril as proper dates. The thought of having a whole life with him all to myself, instead of just stolen moments, felt like tripping over a floorboard and falling into a feather bed, disorienting and delightful. But I had never considered that more of Charlie might mean less of my life here on Augur Lane. Charlie was one of the only people in my life who supported, even encouraged, my commitment to this mad line of work. It was part of the reason that—

I swallowed. My head felt all hot and foggy.

It was part of the reason that I loved him.

I realized Jackaby and Jenny were both watching me closely.

“I—I’m going to go look at a dead body,” I said, straightening. “I’m going to go find clues and interview witnesses. I’m going to go think very, very hard about murder and mayhem and monsters, because that’s what I do.”

Jackaby smiled. He looked like he was about to speak again, but I cut him off.

“And I’m going to go do all that with Charlie,” I said. “I like saving the world with Charlie. We’ll be back this evening.”

Jackaby’s smile wobbled, but he did not stop me as I stepped numbly out the door.

Chapter Seven

The streets of New Fiddleham felt less chaotic with Charlie as my escort. I had never known Mr. Jackaby to take the same route twice, and when he was at the helm, we always spun around so many times that I could never tell which way we had actually traveled or how far we had gone by the time we got there. Charlie and I moved purposefully, and we caught a ride on a public horse-drawn trolley for most of the trip north.

Jackaby had gotten me so flustered, I found myself wondering, for the first few blocks, if Charlie was going to kneel down at any moment, take a ring from his pocket, and ask me the question I was not fully prepared to answer. What would I say if he did? Would I throw my arms around his neck and cry Yes as the gray-haired couple ahead of us turned and made saccharine faces, or would I panic completely and throw myself sidelong from the moving cart in a fit of anxiety? Either option promised a long and awkward return to Augur Lane. Nervous as the notion made me, it was a strangely giddy nervousness.

We passed a building on Prospect Lane with the windows all boarded up. Charlie sighed. The words US OR THEM had been painted across the door in crude strokes. In the absence of tenants, the whole side of the building had been papered with notices. Spade’s edict about “unnatural neighbors” was visible two or three times, along with the faces of a dozen persons of interest. The familiar etching of Charlie’s face was visible in the mix. I winced.

The exciting bubble of a potential future popped as the reality of the past thudded back into my mind. Charlie had very publicly transformed into a frightening beast in the center of town last winter. New Fiddleham did not know that he had spent the rest of that evening saving their lives and mine by risking his own against the real monster. They didn’t know that he continued to risk his life every day to keep their streets safe. They did not know that he continued to act the hero for them long after they had painted him the villain. The wanted posters continued to surface, in spite of Marlowe’s order for them to cease.

If New Fiddleham was ever going to forget the ridiculous rumors about a werewolf in the West End, it wasn’t going to be in the middle of this furor over all things paranormal.

“What are you thinking about?” Charlie said, breaking the silence.

I emerged from my thoughts and looked away from the sad building. “The way things change,” I said, honestly. “It can be a bit overwhelming, that’s all.”

He looked over his shoulder at the wall as we clopped along and nodded solemnly. Suddenly, the little old couple in front of me looked less sweet and adoring and more like potential witnesses, just waiting for their chance to hop off the trolley and tell the nearest constable that the dangerous fugitive had been spotted. Would they recognize him from the posters? Oh—why were we out in public at all?

“You know,” I said, “you don’t owe New Fiddleham anything. You don’t need to help them.”

“Look,” Charlie said as we clipped past Market Street. He was pointing at a man delicately painting enormous letters onto a broad window as we passed. NONNA SANTORO’S, it read, although the RO’S was still just an outline.

“That Italian restaurant?”

“Yes,” he smiled. “They will be opening their doors for the first time very soon. Sweet family. I bought my first meal in New Fiddleham from that man. A couple of meatballs from a street cart were about all I could afford at the time. He’s an immigrant, too. He’s going to do well. His red sauce is amazing.”

“That’s grand for him, then,” I said.

“I like it when doors open,” said Charlie. “Doors are opening in New Fiddleham every day. It is a remarkable time to be alive anywhere, really. Do you think our parents could ever have imagined having machines that could wash dishes, machines that could sew, machines that do laundry? Pretty soon we’ll be taking this trolley ride without any horses. I’ve heard that Glanville has electric streetcars already. Who knows what will be possible fifty years from now, or a hundred. Change isn’t always so bad.”

“Your optimism is both baffling and inspiring,” I said.

“The sun is rising,” he replied with a little chuckle.

I glanced at the sky. It was well past noon.

“It’s just something my sister and I used to say,” he clarified. “I think you would like Alina. You often remind me of her. She has a way of refusing to let the world keep her down.” He smiled and his gaze drifted away, following the memory.

“Alina found a rolled-up canvas once,” he said, “a year or so after our mother passed away. It was an oil painting—a picture of the sun hanging low over a rippling ocean. She was a beautiful painter, our mother. I could tell that it was one of hers, but I had never seen it before. It felt like a message, like she had sent it, just for us to find.

“I said that it was a beautiful sunset, and Alina said no, it was a sunrise. We argued about it, actually. I told her that the sun in the picture was setting because it was obviously a view from our camp near Gelendzhik, overlooking the Black Sea. That would mean the painting was lo

oking to the west.

“Alina said that it didn’t matter. Even if the sun is setting on Gelendzhik, that only means that it is rising in Bucharest. Or Vienna. Or Paris. The sun is always rising somewhere. From then on, whenever I felt low, whenever I lost hope and the world felt darkest, Alina would remind me: the sun is rising.”

“I think I like Alina already. It’s a heartening philosophy. I only worry that it’s wasted on this city.”

“A city is just people,” Charlie said. “A hundred years from now, even if the roads and buildings are still here, this will still be a whole new city. New Fiddleham is dying, every day, but it is also being constantly reborn. Every day, there is new hope. Every day, the sun rises. Every day, there are doors opening.”

I leaned in and kissed him on the cheek. “When we’re through saving the world,” I said, “you can take me out to Nonna Santoro’s. I have it on good authority that the red sauce is amazing.”

He blushed pink and a bashful smile spread over his face. “When we’re through saving the world, Miss Rook, I will hold you to that.”

The rest of the journey was mostly silent, but the awkwardness had fallen away behind us. I leaned in, and Charlie put his arm around my shoulders while we rode. There were some adventures I could not have with Mr. Jackaby.

Our ride came to an end half a mile from our destination, and we walked the rest of the way to the Coolidge Gardens. Technically a public park, the gardens were no simple planter box of geraniums or patch of grass in the middle of a city. The Coolidge Gardens were big. They sat at the northernmost limits of the city, a sprawling three-acre plot situated atop a high hill that overlooked New Fiddleham. It was a manicured Eden of hedges, heathers, and hundreds of varieties of fragrant flowers, whose perfume rolled through the paths and hedgerows and spilled up over the high fence that surrounded the property.

Charlie led us discreetly out of sight of the policemen stationed at the front entrance and along the perimeter until we came to a very old oak tree growing against the border. The tree’s lower branches had been trimmed back to accommodate the barrier, but its upper branches reached over the fence and hung just above the garden. With a quick glance back to ensure we had not been observed, we climbed up and shuffled along the sturdiest branch, dropping down to the soft turf on the other side as quietly as we could.

The walk from there to the actual site of the crime was downright idyllic. Walking with Charlie as the early evening sun came streaming over fields of forget-me-nots and rosebushes, I was beginning to feel that the universe was conspiring to set entirely the wrong atmosphere for the evening’s purposes. Charlie, mercifully, still did not broach the topic of the ring even once on our journey. If he had intended to propose, as Jackaby had warned, then at least he did not seem inclined to do so on our way to a grisly murder site. Credit to Charlie for that.

We came around a fat pink shrub and I shuddered to a halt. Directly ahead of me stood another uniformed policeman. There was no hiding from him; if I had been any closer we might have slow-danced. He was familiar. I had seen him in the precinct a dozen times, reporting officiously to Marlowe. What was his name?

The officer looked as startled as I was, and then his eyes turned to Charlie. Maybe he won’t recognize him, I thought, desperately. Charlie was out of uniform—maybe the man would just take us for young lovers out for a walk in the park. Young lovers who had somehow failed to notice the armed police barricade at the entrance.

“Cane,” the man said.

My heart sank. Charlie Barker was just a man. Charlie Barker had no history beyond last winter. Charlie Cane was a dangerous fugitive.

“Lieutenant Dupin,” Charlie answered. “How is Marie?”

“Walking already,” said Dupin, his face softening. “Growing so fast. Calls me Da. She calls the dog Da, too, and the neighbor’s cat, but I try not to take it too personally.” He coughed and jabbed his chin meaningfully toward me, raising an eyebrow. “Who’s she?”

“She’s here with me,” Charlie said.

“You mean she isn’t,” Dupin corrected. “Because you’re definitely not here.” He sniffed. “Well, then. Standing here, all alone as I am, I feel suddenly compelled to go investigate a noise I might have heard over . . . elsewhere.” He gave me a civil nod, and then added: “Should anyone not be here while I’m away, they would do well to make their not being here brief. The chief investigator sent for the coroner’s boys to collect the body an hour ago. They’ll be along any minute now.”

“Thank you,” said Charlie.

Dupin gave Charlie a pat on the arm as he passed. “You have nothing to thank me for, Cane. You’re not here.”

I heaved an enormous sigh of relief. Commissioner Marlowe knew the truth, but I had assumed everyone else in the police department had turned on Charlie.

“Dupin seems nice,” I said.

“He is an excellent detective.”

“You don’t think he’s going to raise the alarm?”

“Whether he does or not, it sounds like we should be quick about it. Are you ready?”

When one is raised in polite English society, one does not expect to find oneself keeping a mental list of gruesome crime scenes one has visited—and certainly not to silently rank them by quantity of blood and horridness of smells. What one expects to learn is how to dance the polonaise and to make small talk with the viscount at Mother’s garden party and to stuff oneself into an elaborate costume to be presented at court. All things considered, the murder scene was not so bad.

This section of the park opened to a sort of fresh-air amphitheater. The lawn sloped downward, bordered by lush hedges that defined the space and drew the gaze toward a simple stone stage at the center of the clearing. I could easily have pictured a pretentious poetry reading or a fancy wedding ceremony taking place there. Except that the last ceremony performed here had clearly been less fancy and more fatal.

The figure lying on the stage had been covered with a cloth, but I could see the outline of a man’s body. There were candle stubs in an arc around the victim as well, all melted down to nothing. He lay on his back, his legs and arms splayed out as though posed for a rendition of the Vitruvian Man. I tried not to think too hard about the spots of red seeping through the cloth. I stepped closer. On either side of the body were broad patterns, as elaborate as lace embroidery, but drawn with pale yellow lines that had been scuffed and blown away in a few places.

“Cornmeal,” said Charlie. “I made some inquiries downtown. The design is apparently called a veve. Madame Voile recognized it. She has a book about vodou invocations.”

“Vodou?” I said.

“That’s what she said. Doesn’t explain the rest, though.” Charlie gestured to the trees that formed a sort of natural backdrop to the theater. The nearest trunks had each been marred by rough carvings. One had been etched with a pentagram, another with a hexagram, and the one in the center with a sort of cross with a loop at the top. I recognized it as an Egyptian ankh. Jackaby had one or two of those among his relics back home. He had told me they stood for life and death. My mind tried to catalogue the symbols. Pagan, Judaic, Egyptian. What was the pattern?

Some sheer fabric had been draped from their branches as well. It rippled in the gentle breeze behind the stage. The scene was sinister, to be sure, and obviously tragic, but somehow the weight of it felt hollow. I should have been revolted and frightened and overwhelmed—I should have felt at least some distant cousin of the emotions that had left me reeling the first time I saw a dead body—but I wasn’t. I felt something else, instead. It was a subtler sort of unsettling, like a mosquito hum in the back of my mind. Perhaps I had begun to grow numb to the macabre, or perhaps it was simply that the stage for this latest murder was a literal stage, but I found myself curiously unmoved by all the paranormal paraphernalia and supernatural set dressing. What troubled me now was that it felt somehow irritatingly famil

iar, like a morbid moment of déjà vu.

“His name was Steven Fairmont,” Charlie said quietly. “Thirty-five.”

“Has anything been changed since the body was first discovered?” I asked, trying to remember what sort of questions Jackaby would have thought to ask.

“The cornmeal has gotten spread out, but otherwise it looks about the same.”

I walked up to the edge of the stage. The cloth had been folded back to reveal the man’s hand. Just below the wrist, I saw that his arm had been cut. A red, angry symbol had been carved into his flesh—a circle, underscored by a wider half circle with a straight line down from there, bisected halfway down like a cross. My old Classical Mythology courses came drifting back to me. It was the symbol of Hades—or maybe Hermes; I could never remember which was which.

How did the symbol of a Greek god have anything to do with vodou invocations? How did vodou have anything to do with ankhs and pentagrams? The buzzing hum in the back of my mind persisted. Think, Abigail. What was odd about the scene? Well, other than everything, of course. How did all the odd fit together?

It didn’t.

“You have to believe in Old Scratch if you’re going to worship him,” I said, thinking aloud.

“Old Scratch?” Charlie asked.

“Something Mr. Jackaby mentioned back at the station. All of this is wrong. It’s lazy. There’s no reason for someone who believes in vodou spirits to also invoke Hades. These symbols all contradict each other. They’re like a hackneyed vignette of the occult from the cover of an insipid dime novel.”

The hum in the back of my mind suddenly became a clear note. I had read that insipid dime novel. It had been titled The Arcane Assassin or some such. Now I realized why this all looked so familiar! The body, the candles, even the fabric billowing eerily in the wind: the last time I had seen all this, the scene had been rendered in a dramatic woodcut on a bent cover; the details had been poorly defined, but the staging was identical. In that particular installment, if memory served, the naive young protagonists were captured by a dreadful demonic cult. I remembered being disappointed that the big human sacrifice scene didn’t actually go the way it appeared in the etching. If the cover artist had been trying to prove that he had no real personal experience with unsavory occult practices, then he had succeeded. No, I thought, no self-respecting Acolyte of Evil would invoke the dark forces with such heavy use of sheer curtains.

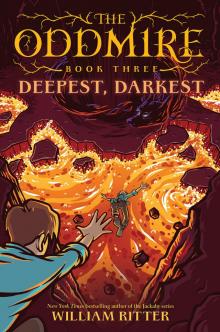

Deepest, Darkest

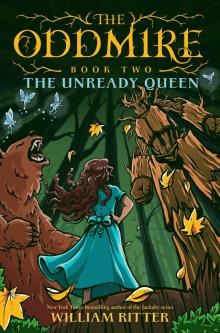

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

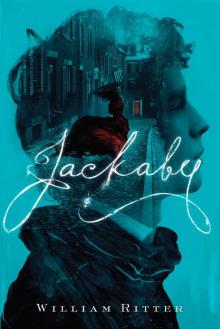

The Unready Queen Jackaby

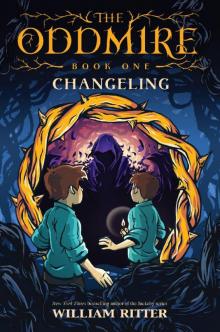

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones