- Home

- William Ritter

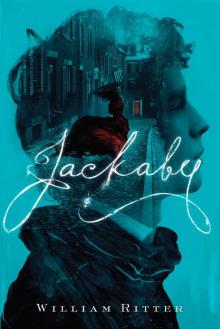

Jackaby Page 3

Jackaby Read online

Page 3

He was speaking in earnest. “Oh yes. I see.” I nodded in what I hoped was a convincing manner. “Sorry. It’s just—at first glance it doesn’t look quite as impressive as all that.”

Jackaby made a noise, which might have been a huff and might have been a laugh. “I have ceased concerning myself with how things look to others, Abigail Rook. I suggest you do the same. In my experience, others are generally wrong.”

My eyes were on my companion as we rounded the corner, and I had to catch myself midstep to avoid barreling into a policeman. Half a dozen uniformed officers kept a crude perimeter around the entrance to a broad, brick apartment building, holding back a growing crowd of curious pedestrians.

“Ah,” said Jackaby with a smile. “We’ve arrived.”

Chapter Four

A tall, barrel-chested policeman looked down his hawk nose at us, and it became apparent that my companion held no more sway here than I did. Jackaby reacted to the obstruction with mesmerizing confidence. The detective strode purposefully up to the officers. “Eyes up, gentlemen, backs straight. Crowd’s getting a bit close, I think. Let’s take it out another five feet. That’s it.”

The officers on the far end with no real view of Jackaby responded to the authoritative voice by shuffling forward, pressing a small crowd of onlookers back a few paces. The nearer officers followed suit with uncertainty, eyes bouncing between their colleagues and the newcomer in his absurd winter hat.

Jackaby stepped between the nearest uniforms. “When Chief Inspector Marlowe arrives, tell him he’s late. Damned unprofessional.”

A young officer with a uniform that looked as though it had once belonged to a much larger man stepped forward timidly. “But Marlowe’s been inside nearly half an hour, sir.”

“Well, then . . . tell him he’s early,” countered Jackaby, “even worse.”

The hawk-nosed policeman with whom I had nearly collided turned as Jackaby made for the doorway. His uncertain gaze became one of annoyance, and, taking a step toward Jackaby, he slid one hand to rest on the pommel of his shiny black nightstick. “Hold it right there,” he called. I found myself stepping forward as well.

“I beg your pardon, sir . . .” I should like to say that I mustered every bit as much confidence as the detective, using my sharp wit and clever banter to talk my way past the barricade. The truth is less impressive. The officer glanced back and I opened my mouth to speak, but the words I so desperately needed failed me. For a few rapid heartbeats I stood in silence, and then, against every sensible impulse in my body, I swooned.

I had seen a lady faint once before, at a fancy dinner party, and I tried to replicate her motions. I rolled my eyes upward and put the back of my hand delicately to my forehead, swaying. The lady at the party had sensibly executed her swoon at the foot of a plush divan. Out on the cobbled streets, my chances of a soft landing were slim. As I let my knees go limp, I threw myself directly into the arms of the brutish policeman, instead, sacrificing my last lingering scraps of dignity.

I gave myself a few seconds, and then blinked up at the officer. Judging by his expression, I don’t know which of us felt more awkward. Anger and suspicion were clearly more natural expressions for him than care and concern, but to his credit, he looked like he was trying.

“Um. You all right, miss?”

I stood, holding his arm and making a show of catching my breath. “Oh goodness me! It must be all this fresh air and walking about. It’s just been so much exertion. You know how we ladies can be.” I hated myself a little bit, but I committed. A few other officers crowding around us nodded in confirmation, and I hated them, too. “Thank you so much, sir.”

“Shouldn’t you . . . um . . . sit down, or something?” the policeman asked.

“Oh, absolutely. I’ll step inside at once, Officer. Yes, sir. I wouldn’t want to stray too far from my escort, anyway. He does worry when I wander off. You’re absolutely right, of course. Thank you, again.”

The big brute nodded, looking a little less out of sorts now that he was being agreed with. I smiled graciously at the circle of uniforms and swept into the building before they had time to reassess the whole affair.

Jackaby regarded me with a raised eyebrow as I closed the door behind me. We found ourselves in a small but well-lit lobby. A wall of miniature, bronze-edged mailboxes stood to our left and a large stairwell, flanked by two fat columns, to our right. Ahead was a door marked EMERALD ARCH APTS: MANAGER with a window looking in on the front desk. Within the little office, another policeman was taking statements from a chap in a doorman’s uniform. Neither paid us any attention.

“That ridiculous little performance of yours should not have worked,” Jackaby said.

“You don’t have to tell me that.” I glanced back at the door. “I’m actually a little offended that it did.”

He chuckled. “So, why did you do it? Surely there are employment opportunities that do not necessitate the brazen deception of armed officials.”

I faltered a moment before I defended myself. “Not so terribly brazen,” I said weakly. “I find most men are already more than happy to believe a young woman is a frail little thing. So, technically the deception was already there, I just employed it in a convenient way.”

He surveyed me through narrowed eyes and then grinned. “You may just be cut out for the job after all, Miss Rook. We’ll see. Stick close.”

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“About to find out.” He ducked his head into the manager’s office. His voice and another responding one came to me in mumbles, and then he popped back out and gestured at the stairs. “Room 301. Shall we?”

Our steps echoed up the stairwell as we started up the first flight.

“So, that policeman just told you where to go?” I asked.

“Yes, very helpful gentleman,” said Jackaby.

“Then, you really are working with the police.”

“No, no, not on this case . . . not as of yet. I simply asked and he told me.” Jackaby swung around the banister as he rounded the curve up to the next flight of stairs.

I thought for a moment. “Is it some kind of magic?” I felt stupid asking.

“Of course not.” Jackaby scoffed at the idea. He paused to examine the banister, and then resumed his trek upward.

“No? Then you didn’t, I don’t know, cast some kind of spell on him or something?”

The man stopped and turned to me. “What on earth makes you think that?” he asked.

“Well, we seem to be sneaking into a crime scene, but you’re not worried about rousing police suspicion, and all your talk about . . . you know.”

“What has that policeman got to be suspicious about? There are half a dozen armed watchmen outside ensuring that only authorized personnel are allowed in. Not unlike your little feigned faint, I merely allowed his assumption to work for me. A far cry from magic spells, Miss Rook, honestly.”

“Well, it’s hard to know what to expect from you. I don’t exactly believe in all this . . . this . . . this occult business. I don’t believe in house spirits, or goblins, or Santa Claus!”

“Well of course not, that’s silliness. Not the spirits or goblins, of course, they’re quite real, but the Santa nonsense.”

“That’s just it! How can you call anything nonsense when you believe in fairy tales?”

“Miss Rook, I am not an occultist.” Jackaby turned on the landing and faced me. “I am a man of reason and science. I believe what I can see or prove, and what I can see is often difficult for others to grasp. I have a gift that is, as far as I have found, unique to me. It allows me to see truth where others see the illusion—and there are many illusions, so many masks and facades. All the world’s a stage, as they say, and I seem to have the only seat in the house with a view behind the curtain.

“I do not believe, for example, that pixies enjoy honey and milk because some old superstition says they do . . . I believe it because when I leave a dish out for them a few times

a week, they stop by and drink. They’re fascinating creatures, by the way. Lovely wings: cobweb thin and iridescent in moonlight.”

He spoke with such earnest conviction, it was difficult to dismiss even his oddest claims. “If you have a . . . ,” I spoke carefully, “a special sight, then what is it that you see here? What are we after?”

Dark shadows clouded Jackaby’s brow. “I’m never sure what others see for themselves. Tell me what you observe, first, and I’ll amend. Use all your senses.”

I looked around the stairwell. “We’re on the second-floor landing. The stairs are wooden and aging, but they look sturdy. There are oil lamps hanging along the walls, but they’re not lit—the light is coming from those greasy windows running up the outer wall. Let’s see . . . There are particles of dust dancing in the sunbeams, and the air is crisp and nipping at my ears. It tastes of old wood and something else.” I sniffed and tried to describe a scent I hadn’t noticed before. “It’s sort of . . . metallic.”

Jackaby nodded. “Interesting,” he said. “I like the way you said all that. The dust-dancing business, very poetic.”

“Well?” I prompted. “What do you see?”

He frowned and slowly continued to the third floor. As we entered the hallway, he reached his hand down and felt the air, as if reaching over a rowboat to trace ripples in the wake. His expression was somber and his brow furrowed. “It gets thicker as we near. It’s dark and bleeding outward, like a drop of ink in water, spreading out and fading in curls and wisps.”

“What is it?” My question came as a whisper, my eyes straining to see the invisible.

Jackaby’s voice was softer still: “Death.”

Chapter Five

The hallway was long and narrow, concluding with a wide window at the far end. It was lit by oil lamps, which cast a sepia glow over the scene. A single uniformed policeman waited outside the apartment immediately ahead. He stood leaning against the frame of the open door, peering back into the room he guarded. A plaque above him declared it apartment 301. The smell, like copper and rot, grew more powerful as we advanced. Jackaby walked ahead of me, and I noticed his step falter slightly. He paused, cocking his head to one side as he looked at the policeman.

At the sound of the stairway door closing, the officer snapped to attention, then relaxed his stance a bit as he made eye contact. He watched our approach, but made no move to engage us. He was clean-cut, his uniform crisp and neatly ironed. His collar was starched, and his badge and buttons shone. His shoes, which looked more like the sharp-toed wingtips of a dress uniform than the sturdy boots of an average beat cop, were buffed so brightly they might have looked more at home on a brass statue than a living body.

“Good day, Officer,” said Jackaby. “Marlowe is waiting for us inside. Don’t want to keep him.”

“No, he isn’t,” said the man, simply. His face was expressionless, studying Jackaby. By the light of the lamps I made him out to be just a year or two older than I. Curls of jet-black hair peeked out from beneath the brim of his uniform cap. He turned to acknowledge me with a polite nod, and his rich brown eyes paused on mine. He smiled shyly, turning his attention quickly back to the detective. My face felt suddenly warm, and I was grateful that he had looked away again.

“Ah, yes,” responded Jackaby, not losing pace, “but he’ll be wanting to see us in there, nonetheless. Bit of a surprise. He’ll be thrilled.”

“I doubt that very much,” said the policeman. His accent was difficult to place—Americanized but faintly eastern European. “I know you,” he said.

Jackaby’s eyebrows rose. “Oh?”

“Yes, you’re the detective. You solve the”—he sought for a word—“special crimes. Inspector Marlowe doesn’t like you.”

“We have a complicated relationship, the inspector and I. What’s your name, then, lad?”

“Charlie Cane, sir. You can call me Charlie. The chief inspector is down the hall right now, talking to witnesses.” He stepped aside, opening the doorway for Jackaby. “I know all about you. You help people. Helped a friend of mine, a baker down on Market Street. No one else would help him. No one else would believe him. He had no money, but you helped anyway.”

“Anton? Good baker. Still saves me a baguette every Saturday.”

“Be quick, Mr. Jackaby.” Charlie glanced up and down the hallway as the detective slid into the room behind him. “And you, Miss—?”

“Rook,” I answered in my most professional tone, hoping I did not sound as flustered as I felt. “Abigail Rook.”

“Well, Miss Rook, will you be examining the room, also?”

“I—of course. Yes, I am Mr. Jackaby’s assistant. I will be, you know, assisting.”

Jackaby shot me a momentary glance from within the room, but he did not correct me. I slipped inside and was immediately overwhelmed by the coppery stench. The apartment had only two rooms. The first was a living area, populated by a small sofa, a writing desk, a bare oak table, and a simple wooden cupboard. Not many decorations adorned the area, but there was a dull oil painting of a sailboat on one wall, and a small framed portrait of a blond woman propped up on the desk.

The door to the next room hung open, revealing the grisly source of the smell. A small halo of dark crimson stained the ground beneath the body. The dead man wore a simple vest and starched shirt, both of which were dyed vivid red at the chest and tattered so thoroughly, it became impossible to discern where clothing ended and flesh began. I felt light-headed in earnest this time, but drew on all my practiced stubbornness not to succumb to a genuine faint. I forced my eyes away from the bloody scene, following the detective instead as he hastened around the first chamber.

Jackaby gave the spartan living room a cursory examination. Wrapping a finger in the end of his scarf, he opened and shut the cupboard, then peeked beneath the table. He lingered briefly by the writing desk, pulling out the chair and returning it. Beside the desk sat another chair, which Jackaby examined more closely, leaning in and delicately brushing a finger along the grain of the wood. Rummaging in his crowded pockets, he removed a blue-tinted vial and held it up, staring at the chair through the glass.

“Hmm.” He straightened and quickstepped to the macabre scene in the bedroom. The vial disappeared back into the coat. I followed, breathing through the fabric of my sleeve—which helped only a little. Jackaby took a rapid tour of this room as well, checking in the closet and under the pillow before bringing his attention to the corpse. I tried to survey the room—to take a careful and deliberate mental inventory of the dead man’s belongings—but my memory of that space remains a faded blur. Almost against my will, my eyes fixed themselves on the horrific sight of that poor body, instead, the picture burning itself into my mind.

“Tell me, Miss Rook,” Jackaby said as he knelt to examine the victim, “what did you notice in that last room?”

I dragged my gaze from the slain body and back to the doorway as I tried to remember anything unusual. “He lives simply . . . lived simply,” I corrected myself awkwardly. My mind peeled very slowly away from the corpse and began to find focus as I considered my surroundings. “I would guess he lived alone. It looks like he had a girl, though—there’s a picture of one in a nice frame over there. Not much food in the cupboards, but a lot of papers on the desk, along with a very modern typewriter, several pens, and at least one spare inkwell. By the letterhead on his stationery, I take it his name was Arthur Bragg. The wastebasket is full of crumpled papers. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was a writer.”

“Huh.” Jackaby glanced back at the door. “Wastebasket?”

I tried to read his expression without looking back at the body. What sort of detective didn’t look in the bin? The men in my adventure magazines were always finding important clues in the bin. “Yes. Back there, just beside the desk.”

Jackaby went back to looking at the body. He lifted a corner of the rug and peered beneath it. “What about the chairs?”

I thought a moment. “The

chairs? Oh, of course—there are two at the writing desk. One where you would expect, but the other—he must have had company!” I looked out again. “Yes, I can see where it’s been taken from its place at the table. Someone was sitting opposite him at his writing desk. That’s why you were so interested in it. Is it strange they didn’t sit around the table, instead? What do you think it means?”

“Haven’t a clue,” answered Jackaby.

“Well, have I got all the important bits? Did you notice something I missed?”

“Of course I did,” said Jackaby, with such a matter-of-fact tone as to almost obscure the arrogance of the statement. “You entirely ignored the clear fact that his guest was not human. I suppose that could, in other circumstances, be inconsequential—but given the state of the man now, it seems rather pertinent.”

I blinked. “Not human?”

“Not at all. Remnants of a distinctly magical aura are all over the chair, and even stronger on the body. Hard to tell what sort of being was here, but old, I can tell. Downright ancient. Don’t feel bad, no way you could have seen that. Now then, what do you notice about the body?”

I paused. “Well, he’s dead,” I said, not wanting to look again.

“Good, and . . . ?”

“He’s clearly lost a lot of blood, having been”—I swallowed hard, keeping my eyes on Jackaby—“torn open, like that.”

“Precisely!” Jackaby grinned at me over the body. “An astute observation.”

“Astute?” I asked. “With all due respect, sir, it’s impossible to ignore. The poor man’s a mess!”

“Ah, but it’s not the wound that’s strange, now is it?”

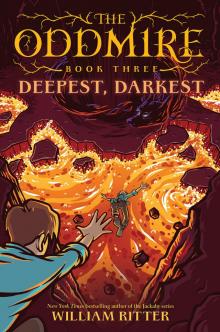

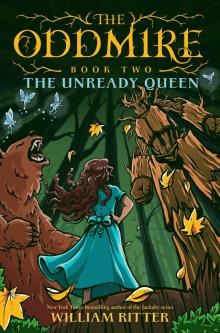

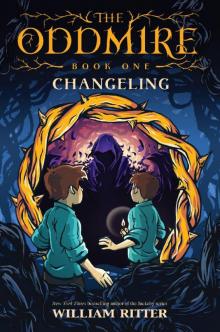

Deepest, Darkest

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

The Unready Queen Jackaby

Jackaby Changeling

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones