- Home

- William Ritter

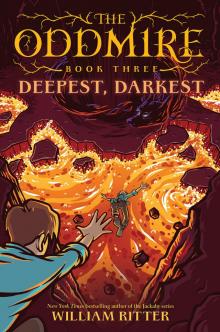

Deepest, Darkest Page 19

Deepest, Darkest Read online

Page 19

The cart hit a bump, and Annie’s shoulder bounced off of a boy sitting beside her. She turned her head to look at him. His freckled cheeks and adorable nose were so familiar. What was his name? She found herself brushing her fingers through his shaggy brown hair.

“Mom?” the boy said, eyes widening. “Mom, are you back?”

Mom. Yes. She was Mom. And this was Cole. How could she have forgotten Cole? Wait. Why were they in a carriage? Hadn’t they just been on an island? She could remember the smell of salt water and the lapping of waves against a shore. Had the island been before or after the cave? Her head hurt. The horses clopped and wheels rumbled along packed dirt roads as she tried to sort it all out.

“Annie?” said a low voice.

Annie turned her head. On the other side of her sat a tall, broad-shouldered man. He was handsome in his way, she supposed, but he was also a ragged mess. His clothes were more dirt than fabric, and his beard was long and scruffy. Annie’s heart was suddenly pounding. Was this fear? No. This didn’t feel like fear. This was something else. It made her whole chest hurt.

She lifted a hand ever so slowly and traced a finger along the man’s jaw. She knew this face. It was different, older, but she knew it.

As if on their own, Annie’s arms reached up and slid behind the man’s neck, and she found herself pulling him closer. Tenderly, the man cupped Annie’s head in his broad hands and pressed his forehead against hers. Their noses brushed ever so faintly, and Annie’s vision went completely blurry. She breathed in shallow gulps and blinked as hot tears streamed down her face.

“What,” she gasped when she could find words again at last, “took you so long?”

Raina listened as her daughter patiently explained, not for the first time, what had happened. It was getting a little easier each time to hold on to the details. “So in the end, the goblins sent word to all the other factions to come and collect their own?” she asked.

“Exactly.” Fable nodded. “And some gnomes came to pick up their long-lost gnome friends, and a bunch of trolls came and picked up their long-lost trolls, and so on. And the humans walked along the peninsula to a human town called ‘A Butt’s Bay’ or something, and Cole’s dad helped us charter horses and carts back to Endsborough. Oh, and Cole has a dad now.”

“None of the forest folk were left behind?”

“Kull and some of the other goblins agreed to stay and shuttle any stragglers back to the forest in their flying balloon things. Candlebeard came out to the island to help, too. He says the hinkypunks will collect as many of those bitter flowers as they can to make a kind of tea that should help everybody sort their brains out again. The ones who got brain-clouded for the longest will probably take a lot longer to set right.”

Raina put a hand to her temple to steady her throbbing head. “Good. That’s all good. And we are currently . . . ?”

“Riding home with the humans. We’re just rolling into Endsborough now.”

In another few minutes, Fable was helping Raina out of the carriage. Raina could see one of her daughter’s friends helping Annie Burton out of another cart, parked just ahead of theirs. A crowd had already begun massing around them, and the air was abuzz with chatter. A woman in a clean white apron had wrapped her arms around a man in faded, dirty coveralls. She was laughing and crying, and he wasn’t saying much at all, but he hugged her back.

It did not take long for the fear and excitement and confusion swirling around the town to find its focus on Fable and Raina.

“That’s her,” someone hissed in a loud whisper. “Queen of the Deep Dark.”

“Pardon me, Your, um, Dark Majesty?”

Raina took a steadying breath and turned her eyes toward a townsperson. It was a broad-chested man in worn trousers and a plaid shirt. He spoke rather timidly for his size.

“Don’t mean to offend, but”—he glanced around—“was this . . . you?”

“Was what me?” asked Raina.

The man in plaid looked nervous. “All of it?”

“The roads are cracked all over,” a woman behind him said. “The old mill’s roof collapsed, and I hear there was a sinkhole out by the Warner place so big it swallowed up Jim Warner’s barn. A lotta folks were real worried Old Jim went down with the dang thing, on account of they couldn’t find him anywhere. We’re right glad to see him with you.”

“What was that about my barn?” said Old Jim.

“Been a strange one,” another voice from the crowd added. “Horses have been spooked all day, and the whole ground feels so hot you could fry an egg on the pavement, but the air is cool as a spring breeze.”

“This is another Wild Wood thing, isn’t it?” said the original man in plaid. “I thought we were all getting along these days. Did we do something wrong?”

“Did you do something wrong?” said Raina. “I don’t know. Probably. You usually do.”

“The Wild Wood didn’t do this!” Fable said, climbing up on the step of the carriage to address the crowd. “They’re just as confused by it as you are. But you can all stop worrying. It’s over now.”

“Stop worrying?” a woman answered. “There’s a crevice running through our hayfield makes it look like somebody snapped it in two like a cracker! Goes so deep, I’m not too keen to climb down to see if it even has a bottom!”

“Back up now,” Old Jim said. “Was it my whole barn?”

“Okay, so there might still be a few things to worry about while we put the town and the forest back together,” said Fable. “But everybody is safe now, and that’s the important bit.”

“We just have to take your word for it?” asked a man toward the middle of the crowd. “I don’t much like sitting around and waiting for the next big disaster. I work down in those mines. Know a lot of guys who refuse to go back tomorrow. We just want to watch our own backs. Is there anything we can do?”

“Well, actually,” said Fable, “there is one thing you could do.”

That afternoon, Madam Root heard the clattering of the kobolds rolling pebbles through the passages as they played. A tinkling chime in the mix caught her ear, and she glanced down. One of the bristly creatures held a polished silver coin in its tiny hands. It squeaked triumphantly. At its feet were a handful of rough gemstones.

Madam Root blinked. “Where under earth did you find those?”

Before the kobold could answer, the echoes reached her ears. They were the voices of men, miners setting foot tentatively into the tunnels above her—no doubt surveying the extent of the damage since the great serpent went back into hibernation. The humans were speaking with the hushed, reverent tones of nervous sinners in a church. Madam Root strained her ears.

“. . . and she dresses all in gray. Some people say she’s a spirit. You’ll never see her properly, but she’s always watching. I heard she helps miners find their way when their lamps go dark.”

“I heard she can walk through solid stone,” came another voice.

“I heard she can turn herself into a cave bat,” said a third.

“I heard if she kisses you, you can see in the dark.”

“I heard it all,” agreed the first voice. “And y’all better believe it, every word. Know one thing for certain, long as I’m working these tunnels, you’d best not let me catch you disrespecting our Lady of the Mountain.”

Madam Root smiled. For many months after, her kobolds would dance giddily in piles of shiny coins and polished stones and even the occasional ham sandwiches that awaited them reliably in the tunnels each night.

The Echo Point Mining Company, in turn, although it had never produced anything in the way of precious metals, would tap into an unexpected silver vein that season and turn out more profit in a single month than the entire operation had seen in the past decade.

Thirty-One

“That’s the last o’ the blighters,” Kull said as Candlebeard helped the addled hob out of his airship. “You’ll get her sorted before ya turn

her out into the woods?”

Candlebeard nodded and led the wobbling hob away by the elbow.

“Grand,” said Kull.

He was alone in the clearing now. Kull knew this stretch of the Wild Wood better than he knew his own horde. He had spent thirteen years crossing through this field on his way to check in on Cole and Tinn. He took a deep breath.

In another few minutes he had prepared the little engine in the dirigible and was just getting ready to untie the anchor ropes when he heard footsteps in the underbrush behind him.

“Oi! Yer na sneakin’ up on me,” he called out. “Might as well show yourself, ya fat-footed gobby!”

“Sorry,” said a voice that made Kull’s insides spin in circles. “My lesson on sneaking got canceled.” Tinn plodded out of the bushes with slow, labored steps. He was holding one arm against his chest. His face was scratched and bruised and he looked sunburned all over.

Kull made a noise like a lizard choking on a pinecone.

“Are you . . . are you crying?”

“Of course I’m na cryin’, ya daft numpty!” Kull wiped snot and tears away from his face with the back of his arm. “Allergic ta havin’ my heart smashed all ta bits, thass all. Otch! Come here, my boy!”

Kull was not a hugger. Goblins in general tended to express fond emotions in more concussive ways—and occasionally with biting—but because it had mattered to Tinn, he had agreed to practice.

“That was your best one yet,” Tinn told him when the goblin finally let go.

Kull coughed and waved him away. “Where’ve ya been? Yer poor family’s worried out o’ their minds over ya!”

When Kull had properly composed himself, they settled into the airship, and Kull coaxed the engine back to life while Tinn related every piece of his eventful day.

“So then the kobolds let me out up on the surface,” finished Tinn. “They didn’t drop me off anywhere close to home, but I’ve done enough hanging out with Fable in the forest to get my bearings pretty quick. And—oh, man—fresh air never tasted so good, so I’m not complaining.”

Kull shook his head, astonished. “I’ll let Chief Nudd know the horde’s in debt to the Lady o’ the Mountain an’ her wee beasties.”

“Whoa.” Tinn glanced out over the Wild Wood as it glided slowly beneath them. “There’s huge holes all over the forest. That one down there’s practically a valley. It’s going to take Fable and her mom forever to get things back to the way they were before.”

Kull snorted. “Why would they waste their time with that?” Tinn looked at him. “Things dinna ever go back ta the way they were. Thass na how life works. Things change. It’s what they do. It’s like a great big Turas Bàis. Old forest had ta die so a new one could live. Still the same forest. Maybe different will be better—eventually. Give it time.”

A few minutes later, Kull set the balloon down near the boys’ favorite climbing tree and walked with Tinn up the winding path. It felt profoundly strange to set foot so openly in human territory—but Tinn was still unsteady on his tired legs, and Kull was not about to send him limping home unattended. He stopped when they reached the front walk.

Through the big living room window, they could see Tinn’s mother sitting on the brown sofa with her back to the window. Cole was in the armchair across from her, waving his hands as he spoke. By the look of it, he was regaling her with their underground adventures. It appeared to be a good story.

Joseph Burton emerged from the kitchen. Even from outside, Tinn could see that his hair looked clean, his face had been freshly shaved, and he was wearing one of his old shirts from the cedar chest in the attic. He looked even more like Cole. He was carrying three steaming mugs, two of which he passed to Cole and Annie.

“That would be hot chocolate,” said Tinn. “They look happy together.”

Kull chewed on his lip. If not for the old goblin’s meddling all those years ago, the scene in front of them might have been that poor family’s every day for the past thirteen years. Without his meddling, Tinn would have never been a part of it at all.

“Aye. They do look happy,” Kull said. “Is that . . . good?”

Tinn nodded. “Yeah,” he said. “That’s good. I kinda thought I would feel more jealous about Cole getting his dad back. He wanted it so bad, and I was just worried about what it meant for me. But this”—he watched as Cole and Joseph clinked hot chocolate mugs—“this is nice, I think. Like maybe Cole is going to be okay without me.”

Kull’s eyebrows shot up on his wrinkled forehead. “He likely to be without ya any time soon?”

“I don’t know,” said Tinn. “It’s always just been me and Cole. But I hear things don’t ever go back to the way they were.”

Annie Burton turned her head slowly toward the window, and Tinn saw the melancholy in her eyes. He waved, weakly, and she started when she saw him. For a silent moment, her eyes just widened, and then she was off the couch and rushing for the door.

Tinn glanced down to say goodbye, but by the time the front door flew open, Kull was already gone. The azalea bush on the edge of the property rustled and fell still.

The next few minutes were a whirlwind of hugs and fussing and questions—and Tinn found himself more or less carried back over the threshold. Vaseline and iodine and bandages and ice packs were applied in rapid succession, and by the time Tinn had a moment to himself, he felt almost more exhausted than he had been when he was slogging home through the forest. But he was home.

Cole held the door for his father as Joseph Burton stepped out onto his back porch for the first time in thirteen years. Joseph sniffed in deeply and breathed out a happy sigh. “Look at that garden. You were probably too young to remember a great big bramble that used to come right up to the back of the house. Your mom and I spent hours fighting that thing.”

“I remember the bramble,” said Cole.

“Oops. Your shoe’s untied, kid. Want me to help you with that?”

“I can tie my own shoe,” said Cole.

“Yeah. I mean. Of course you can tie your shoes.” He rocked on his heels as Cole sat down on the step to fix his laces. “Oh, hey. I can still teach you how to tie a necktie, though. Never know when you might need to dress up fancy for a special occasion.”

“Oh,” said Cole. “Mom already showed us how to tie a tie. For a dance. At school. Tinn’s always come out crooked, but I got mine down pretty good.”

“Ah. Right. Good. That’s good. You boys had your first dance, then, too? That’s great. Great.”

“Yeah.”

They were quiet. Joseph leaned on the porch railing.

“Are you okay, Dad?”

“Mm? Why wouldn’t I be okay? I’m home. I’ve got my wife and my healthy son—my sons. Both of them, because I have two. See? I’m even starting to remember things for longer. I’m great.”

Cole watched the way his father’s eyes crinkled and the way the dimples on his cheeks framed his broad grin. The man had shaved off his scruffy beard with the razor that Annie had kept tucked away in the back of the linen cupboard even after all this time. He looked ten years younger than the ragged man they had found in the tunnels. “I like your face without the beard,” Cole said aloud.

“Yeah?” Joseph rubbed his cheeks. “Well, thanks. I like your face, too, kid. Although—you’ll be needing to start shaving your beard any minute now. Don’t think I don’t see those whiskers starting to come in.” His smile sagged for a moment. “You’ve probably already learned how to shave?”

Cole shook his head. “Nope. Not yet.”

“Well then.” Joseph’s eyes sparkled and he sat down beside his son. “Maybe there’s still a few things I can show you.”

“Yeah.” Cole leaned in, and Joseph put an arm around his shoulder. “I’d like that.”

They listened to the crickets chirp and the wind rustle the willow tree.

Thirty-Two

Annie Burton sighed contentedly as she watched

through the window. She sipped her tea, feeling the hot steam on her face. On her own, with two troublemaking boys underfoot, it had been a very long time since Annie had finished an entire cup of tea before it went cold. She was thoroughly looking forward to the experience.

Tinn was in the living room petting Chuffy. That cat had known the boys their entire lives. She had cuts in both of her felted ears and didn’t see as well as she used to—but she still always managed to find the one person in the house who most needed to be petting her. She purred merrily in Tinn’s lap, but his eyes were miles away.

“Hey, big guy,” said Annie. “How come you’re not out back with your brother and your dad?”

“I thought I’d let them have a little time to themselves,” said Tinn.

Annie nodded. She sat down next to him on the comfy brown sofa. “You don’t have to do that, you know.”

“Do what?”

“Run away from him. He’s a good man.”

“I know. He seems nice. He and Cole just need each other right now, I think.”

“He wants to be your dad, too.”

“Yeah. He told me that. It’s good to hear.”

“But . . . ?”

“But . . . I already have a dad. Kull’s my dad.”

Annie nodded. She peered into the steam rising from her cup for a minute before speaking again. “A long time ago I thought I had just one son,” she said.

Tinn looked up at her.

“But then it turned out I had two. And do you know what I learned once I accepted that I had two sons?”

“That one of those sons was a goblin?”

“That when I allowed myself to love both of my sons, I wound up with twice as much love to go around. I didn’t have any less of one son just because I had more of another. It’s funny how that works, isn’t it? Know what else I learned?”

“That you loved your changeling son a teensy bit more after all because he didn’t break that vase your aunt gave you?”

Deepest, Darkest

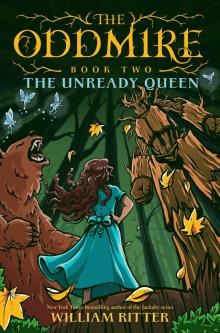

Deepest, Darkest The Unready Queen

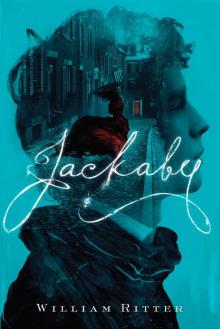

The Unready Queen Jackaby

Jackaby Changeling

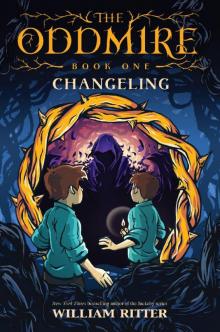

Changeling The Dire King

The Dire King Ghostly Echoes

Ghostly Echoes Beastly Bones

Beastly Bones